Introduction to Vicarious Liability

Definition and Meaning

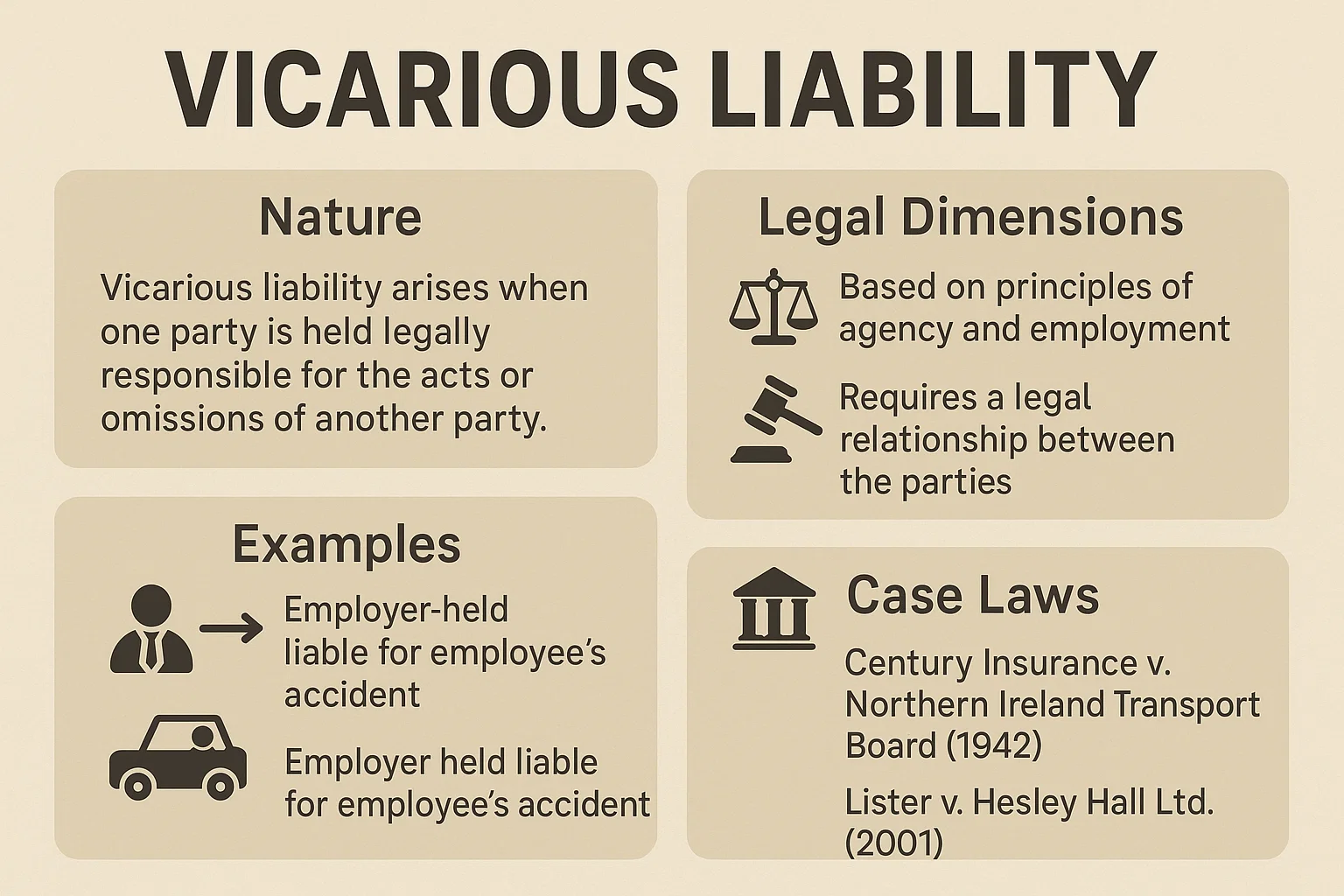

Vicarious liability is a legal principle where one person is held liable for the wrongful acts committed by another, typically in a relationship where one has authority or control over the other. Most commonly, it arises in employer-employee relationships. The term “vicarious” comes from the Latin word vicarius, meaning substitute. Hence, it implies that someone is held responsible not for their own actions, but for those of another person.

This concept plays a critical role in civil law, particularly tort law, where compensation is sought for harm or injury. Vicarious liability doesn’t depend on the fault of the person held liable but rather on their relationship to the actual wrongdoer.

Historical Background

Vicarious liability can be traced back to English common law. It emerged from a time when the notion of a master being responsible for his servant was rooted in the belief that he should control those under his employment. Over time, the doctrine was refined through judicial decisions to establish clearer criteria for when and how liability transfers.

In India, the concept was inherited through British colonization and further developed through landmark rulings. Indian courts have molded the principle to align with local jurisprudence, often using it to ensure justice in complex liability situations.

Importance in Tort Law

The significance of vicarious liability lies in its capacity to ensure that injured parties receive compensation from someone capable of paying damages. It acknowledges practical realities: the person committing a wrongful act (like an employee) may not have the resources to pay compensation, whereas the employer likely does.

From a policy perspective, it encourages employers to supervise and train employees effectively and ensures that organizations are accountable for the conduct of their workforce. It’s not just about punishment—it’s about prevention, responsibility, and justice.

Nature of Vicarious Liability

Core Principles of Vicarious Liability

At its core, vicarious liability operates on the doctrine of respondeat superior, a Latin term meaning “let the master answer.” This principle underscores that a person in a superior position (like a master or employer) must take responsibility for the actions of those under their control, provided those actions were committed in the course of their employment.

This form of liability is strict—meaning it does not require proof of intent or negligence on the part of the person being held liable. The primary elements necessary for this type of liability include:

- A legally recognized relationship (e.g., master-servant).

- A wrongful act or omission.

- The act must be committed within the scope of the authorized relationship.

Difference Between Direct and Vicarious Liability

Direct liability is when a person is held accountable for their own actions. For instance, if a shopkeeper spills oil on the floor and someone slips, the shopkeeper is directly liable. On the other hand, vicarious liability arises when someone else commits the act, but the responsibility transfers due to a relationship or legal obligation.

The distinction is crucial because it determines the defenses available and the manner of proving the case. In vicarious liability, establishing the relationship and the act within scope is more critical than proving personal negligence.

Conditions for Vicarious Liability to Arise

For vicarious liability to be established, certain conditions must be met:

- Existence of a relationship: Typically, this is an employer-employee or principal-agent relationship.

- Act within the course of employment: The wrongful act must occur during employment or within the scope of the authority given.

- Connection to the job: The wrongful act should be reasonably connected to the duties assigned, even if it was performed in an unauthorized or improper way.

If these conditions are satisfied, courts generally hold the employer liable, even if they did not directly commit or endorse the wrongful act.

Master and Servant Relationship

Who is a Master and Who is a Servant?

In legal terminology, a “master” is someone who employs another person (a “servant”) to do work under his or her control. The servant is bound to follow the master’s instructions and performs tasks under direct supervision. This dynamic forms the bedrock of vicarious liability cases.

For example, a delivery driver working for a logistics company is considered a servant. The company is the master. If the driver negligently causes an accident while making deliveries, the company may be held vicariously liable.

Control Test and Other Determinants

The most common test used by courts to determine a master-servant relationship is the “control test”. This test examines whether the employer has the right to direct what the employee does and how they do it. The greater the control, the more likely the relationship fits the master-servant model.

Other relevant tests include:

- Integration Test: Whether the work done by the individual is integral to the employer’s business.

- Multiple/Economic Reality Test: Looks at various aspects, such as the source of payment, control, equipment ownership, etc.

No single test is definitive, but courts use them to analyze relationships on a case-by-case basis.

When is a Master Liable for the Acts of a Servant?

A master is liable for the acts of the servant only if the act was committed “in the course of employment.” This includes:

- Acts authorized by the master.

- Unauthorized acts closely connected with authorized duties.

- Negligent acts while performing job-related duties.

However, a master is not liable when the servant acts outside the scope of employment—commonly referred to as a “frolic of his own.” For instance, if a delivery driver deviates for personal reasons and causes harm, the company may not be liable.

Key Case Laws under Master-Servant Doctrine

- State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati (AIR 1962 SC 933)

A government vehicle driven negligently by a government employee caused a fatal accident. The court held the government vicariously liable for the wrongful act of its employee. - Limpus v. London General Omnibus Co. (1862)

A bus driver, despite explicit instructions, raced another bus and caused an accident. The company was held liable as the act was committed during employment. - Twine v. Beans Express Ltd. (1946)

A driver picked up unauthorized passengers, and an accident ensued. The court ruled against liability as the act was outside the scope of employment.

State Liability

Evolution of State Liability in Tort

In ancient times, the king could do no wrong. This principle led to sovereign immunity—a doctrine where the state was immune from legal action. However, modern democracies have evolved to recognize state liability, especially when public servants commit torts.

Indian jurisprudence, post-independence, gradually began to distinguish between sovereign and non-sovereign functions. The state cannot claim immunity in cases involving the latter.

Sovereign vs Non-Sovereign Functions

The doctrine of sovereign immunity has often been challenged, especially when it results in injustice. Indian courts have adopted the distinction between sovereign and non-sovereign functions to determine when the state can be held liable.

- Sovereign functions involve core government roles such as defense, foreign affairs, and lawmaking. In such cases, the state may not be held liable for the actions of its agents.

- Non-sovereign functions include commercial or administrative activities like maintaining roads, providing transportation, or managing hospitals. In these cases, the state can be vicariously liable.

This distinction was clearly drawn in cases like Kasturi Lal v. State of U.P. (AIR 1965 SC 1039), where the Supreme Court granted the state immunity because the tortious act occurred while performing a sovereign function (policing).

Leading Judicial Decisions

- State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati (1962)

This landmark decision marked a turning point. The Supreme Court held that the state was liable for the negligence of its employee who caused a fatal accident while driving a government vehicle. The Court ruled that driving a vehicle for official work is not a sovereign function. - Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa (1993)

A boy died in police custody. The Court emphasized state accountability and awarded compensation. It reaffirmed that fundamental rights violations could not be shielded by sovereign immunity. - Common Cause v. Union of India (1999)

The Court emphasized that the state is liable for torts committed by public servants while performing non-sovereign functions, especially where fundamental rights are infringed.

Case Law Illustrations

Here are a few more examples that illustrate how courts assess state liability:

| Case | Facts | Verdict |

| Basava Kom Dyamogouda v. State of Karnataka (1977) | Police lost seized gold ornaments. | Held: State liable for negligence. |

| Smt. Shyam Sunder v. State of Rajasthan (1974) | Accident caused by state-run transport bus. | Held: Vicarious liability applied. |

| Jay Laxmi Salt Works v. State of Gujarat (1994) | Salt works flooded due to breach in dam. | Held: State liable for negligence in non-sovereign function. |

These cases underscore that while the state may escape liability for actions under sovereign authority, it remains accountable for commercial, administrative, and public welfare activities.

Strict and Absolute Liability

What is Strict Liability?

Strict liability is a legal doctrine where a person is held liable for damage caused by their actions or property without the need to prove negligence or intent. This principle is typically applied in cases involving hazardous or dangerous activities.

The classic case that established this doctrine is Rylands v. Fletcher (1868). In this case, the defendant built a reservoir on his land, which burst and flooded the plaintiff’s coal mines. The Court ruled that anyone who brings something onto their land that is likely to cause harm if it escapes is strictly liable.

Key Elements of Strict Liability:

- Dangerous thing brought onto the land.

- Non-natural use of land.

- Escape of the harmful thing.

- Damage caused as a result.

The defendant is liable even if they took all reasonable care to prevent harm.

Exceptions to Strict Liability

However, there are some recognized exceptions:

- Plaintiff’s fault: If the damage was due to the plaintiff’s negligence.

- Act of God: Natural events like earthquakes.

- Act of a third party: If a third party, beyond the defendant’s control, caused the escape.

- Consent of the plaintiff: If the plaintiff consented to the danger.

- Statutory authority: If the activity was authorized by law.

These exceptions show that strict liability is not absolute in nature and that courts do allow certain defenses based on the circumstances.

Development of Absolute Liability in India

The concept of absolute liability was pioneered by Indian courts to address the limitations of strict liability. Unlike strict liability, absolute liability has no exceptions. It was developed to deal with the dangers posed by modern industrialization.

This doctrine was laid down in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987), following the Oleum gas leak in Delhi from a fertilizer plant operated by Shriram Foods and Fertilizers. The Supreme Court declared:

“An enterprise engaged in a hazardous or inherently dangerous activity owes an absolute and non-delegable duty to the community…”

The court emphasized that companies carrying out such activities must ensure that no harm is caused to anyone. If harm does occur, they are absolutely liable, regardless of precautions taken.

Relevant Cases (Rylands v Fletcher, MC Mehta v Union of India)

| Case | Jurisdiction | Principle Laid Down |

| Rylands v. Fletcher (1868) | UK | Introduced strict liability for escape of dangerous substances. |

| M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987) | India | Introduced absolute liability with no exceptions. |

| Indian Council for Enviro-Legal Action v. Union of India (1996) | India | Reiterated absolute liability for hazardous industries. |

These cases form the backbone of environmental tort law in India and provide a solid foundation for regulatory mechanisms in industrial operations.

Joint Tortfeasors

Definition and Legal Position

Joint tortfeasors are two or more persons who act together to commit a tort or whose independent acts combine to cause a single harm. Under this doctrine, all tortfeasors are jointly and severally liable, meaning the injured party can sue any one or all of them for full compensation.

For instance, if two doctors perform a negligent surgery together, and the patient suffers injury, both can be held liable as joint tortfeasors.

Principles Governing Joint Liability

The doctrine is governed by three main principles:

- Common design: Where tortfeasors act in concert.

- Concurrent negligence: Independent negligent acts that result in a single injury.

- Joint enterprise: Participants in a shared activity leading to harm.

Joint liability ensures that the injured party isn’t denied justice due to difficulty in proving who exactly caused the harm.

Contribution and Apportionment

In cases involving joint tortfeasors:

- The plaintiff may claim the entire damages from any one defendant.

- The defendant who pays can seek contribution from the other tortfeasors.

- Courts may apportion the liability based on degree of fault.

This mechanism promotes fairness by ensuring compensation to the injured while allowing internal adjustment among tortfeasors.

Landmark Judgments and Case Studies

- Koursk Case (1924)

Collision between two ships caused by combined negligence of both. Both parties held jointly liable. - Khushro S. Gandhi v. N.A. Guzdar (1970)

The Bombay High Court ruled that joint tortfeasors are jointly and severally liable, and contribution is permitted under equity principles. - Amrit Lal v. Government of India (1976)

The Court allowed recovery of full damages from the government, despite multiple parties being involved in a railway mishap.

These cases highlight how courts uphold the interests of justice by ensuring collective accountability.

Differences Between Vicarious, Strict, and Absolute Liability

Comparative Table

To understand the distinctions clearly, here’s a comparative table outlining the differences between vicarious, strict, and absolute liability:

| Feature | Vicarious Liability | Strict Liability | Absolute Liability |

| Basis | Relationship-based (e.g., master-servant) | Risk-based | Risk-based with zero exceptions |

| Fault | No personal fault required | No negligence needed | No negligence or exceptions |

| Defenses | Possible if the act was outside the scope of employment | Certain exceptions allowed (Act of God, third party, etc.) | No defense allowed |

| Liable Party | Master/employer or principal | Person who owns/dominates the hazardous activity | Owner of hazardous activity or enterprise |

| Origin | Common law principle | Originated from Rylands v. Fletcher | Developed by Indian judiciary |

| Example Case | State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati | Rylands v. Fletcher | M.C. Mehta v. Union of India |

Applicability in Modern Law

All three forms of liability play critical roles in modern legal systems but differ significantly in scope and applicability.

- Vicarious liability is most prevalent in employment contexts and public authority accountability. It ensures that institutions, whether public or private, do not escape responsibility for the actions of those under their control.

- Strict liability applies primarily to situations involving dangerous substances or conditions—like chemicals, explosives, or large-scale machinery.

- Absolute liability, particularly in India, is used in environmental and industrial disasters. Given the growing risks associated with industrialization and pollution, this doctrine has become a cornerstone of environmental justice.

These doctrines aren’t mutually exclusive but are used in tandem depending on the nature of the harm and the relationship between the parties involved.

Vicarious Liability in Modern Context

Employer’s Liability in Gig Economy

The rise of the gig economy has introduced a new challenge to traditional vicarious liability principles. Companies like Uber, Swiggy, and Zomato claim that their workers are independent contractors, not employees, to avoid liability for their actions. This classification is under scrutiny globally.

However, courts are increasingly considering the control and economic dependency that gig workers have on platforms. For example:

- In the UK, Uber drivers were declared “workers,” not independent contractors, giving them protection and imposing responsibilities on Uber.

- In India, although the judiciary has yet to deliver landmark rulings, consumer complaints and labor disputes are pushing for reclassification.

The key legal question is: Does the company have sufficient control over the individual’s work? If yes, vicarious liability may still apply.

Vicarious Liability in Cyber Law

In the digital age, liability extends to online platforms and service providers. Social media giants, internet service providers, and website hosts may be held vicariously liable for the content posted by users, especially if:

- They fail to remove illegal or harmful content after being notified.

- Their platform design or algorithms amplify such content.

Example: If a user uploads defamatory content on a platform and the company doesn’t act after being informed, it may face vicarious liability for allowing harm to persist.

Some countries now have clear legislation on intermediary liability, while others are relying on judicial interpretation.

State and Police Misconduct

Vicarious liability is increasingly being invoked in cases of police brutality and custodial deaths. Though the state may try to shield itself under sovereign immunity, courts are piercing that veil, especially when constitutional rights are violated.

For instance, in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997), the Supreme Court laid down guidelines for arrest and detention to prevent custodial abuse. Any violation can now attract both personal and vicarious liability against the police force and the state.

Modern vicarious liability thus stretches far beyond employment—it is now a key tool for ensuring institutional accountability in a wide variety of settings.

Case Studies and Practical Examples

Indian Case Examples

- M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Oleum Gas Leak Case)

The Supreme Court imposed absolute liability on the industry, departing from the rule in Rylands v. Fletcher and emphasizing the need for a higher standard in the context of industrial activities. - Vidhyawati Case (1962)

Government held liable for the negligence of a state-employed driver, marking a milestone in state liability under non-sovereign functions. - Kasturi Lal v. State of UP (1965)

In this case, the state was held not liable due to the act being under a sovereign function (policing). The court distinguished it from cases involving non-sovereign functions. - Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa (1993)

Compensation was awarded for custodial death. The court ruled that the state cannot claim immunity when fundamental rights are breached. - Indian Medical Association v. V.P. Shantha (1995)

Doctors and hospitals were held liable under consumer protection laws, clarifying how institutions can face vicarious liability for medical negligence.

International Case Examples

- Lister v. Hesley Hall Ltd. (UK, 2001)

A school was held vicariously liable for sexual abuse committed by a warden. The court emphasized the “close connection” between the employee’s role and the wrongful act. - Bazley v. Curry (Canada, 1999)

A non-profit organization was found liable for abuse committed by its employee in a children’s home. The court underlined the need to provide justice to victims even when the wrongdoer was a single individual. - Majrowski v. Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust (UK, 2006)

The NHS Trust was held vicariously liable for harassment committed by an employee, extending liability under the Protection from Harassment Act.

These real-world examples show the extensive and evolving application of vicarious, strict, and absolute liability across various sectors and legal systems.

Conclusion

Vicarious liability, along with its cousins—strict and absolute liability—plays an essential role in shaping modern tort law. These doctrines are not merely legal constructs; they are tools of social justice, accountability, and deterrence. Whether it’s an employer, the state, or a corporation, the law ensures that no one can hide behind hierarchy or structure to escape responsibility.

In a world where complex organizational structures and technologies often shield the actual wrongdoer, these liability doctrines ensure that the victim is not left without remedy. From master-servant relationships to state negligence and industrial disasters, the principle continues to evolve and adapt to new societal challenges.

It’s vital that courts and lawmakers continue to uphold and refine these principles to ensure justice is both accessible and effective in today’s dynamic legal landscape.

FAQs

1. What is the main purpose of vicarious liability?

The main purpose is to ensure that victims receive compensation from someone who has the financial capacity and control to prevent the wrongdoing, usually the employer or the state.

2. Can an independent contractor create vicarious liability?

Generally, no. Vicarious liability typically applies to employees, not independent contractors, unless the contractor was treated as an employee based on control or integration.

3. How does vicarious liability affect employers?

Employers must ensure proper training, supervision, and background checks of employees because they can be held liable for wrongful acts committed by employees during employment.

4. Is strict liability applicable in criminal law?

Strict liability does exist in criminal law, particularly in regulatory offences (like environmental violations), where intent or knowledge isn’t required to prove guilt.

5. How is state liability different from master-servant liability?

State liability involves government responsibility for wrongful acts of public servants, often limited by sovereign immunity. Master-servant liability pertains to private relationships and does not generally benefit from such immunity.

Vicarious Liability: Nature and Legal Dimensions with Examples and Case Laws

Introduction to Vicarious Liability

Definition and Meaning

Vicarious liability is a legal principle where one person is held liable for the wrongful acts committed by another, typically in a relationship where one has authority or control over the other. Most commonly, it arises in employer-employee relationships. The term “vicarious” comes from the Latin word vicarius, meaning substitute. Hence, it implies that someone is held responsible not for their own actions, but for those of another person.

This concept plays a critical role in civil law, particularly tort law, where compensation is sought for harm or injury. Vicarious liability doesn’t depend on the fault of the person held liable but rather on their relationship to the actual wrongdoer.

Historical Background

Vicarious liability can be traced back to English common law. It emerged from a time when the notion of a master being responsible for his servant was rooted in the belief that he should control those under his employment. Over time, the doctrine was refined through judicial decisions to establish clearer criteria for when and how liability transfers.

In India, the concept was inherited through British colonization and further developed through landmark rulings. Indian courts have molded the principle to align with local jurisprudence, often using it to ensure justice in complex liability situations.

Importance in Tort Law

The significance of vicarious liability lies in its capacity to ensure that injured parties receive compensation from someone capable of paying damages. It acknowledges practical realities: the person committing a wrongful act (like an employee) may not have the resources to pay compensation, whereas the employer likely does.

From a policy perspective, it encourages employers to supervise and train employees effectively and ensures that organizations are accountable for the conduct of their workforce. It’s not just about punishment—it’s about prevention, responsibility, and justice.

Nature of Vicarious Liability

Core Principles of Vicarious Liability

At its core, vicarious liability operates on the doctrine of respondeat superior, a Latin term meaning “let the master answer.” This principle underscores that a person in a superior position (like a master or employer) must take responsibility for the actions of those under their control, provided those actions were committed in the course of their employment.

This form of liability is strict—meaning it does not require proof of intent or negligence on the part of the person being held liable. The primary elements necessary for this type of liability include:

- A legally recognized relationship (e.g., master-servant).

- A wrongful act or omission.

- The act must be committed within the scope of the authorized relationship.

Difference Between Direct and Vicarious Liability

Direct liability is when a person is held accountable for their own actions. For instance, if a shopkeeper spills oil on the floor and someone slips, the shopkeeper is directly liable. On the other hand, vicarious liability arises when someone else commits the act, but the responsibility transfers due to a relationship or legal obligation.

The distinction is crucial because it determines the defenses available and the manner of proving the case. In vicarious liability, establishing the relationship and the act within scope is more critical than proving personal negligence.

Conditions for Vicarious Liability to Arise

For vicarious liability to be established, certain conditions must be met:

- Existence of a relationship: Typically, this is an employer-employee or principal-agent relationship.

- Act within the course of employment: The wrongful act must occur during employment or within the scope of the authority given.

- Connection to the job: The wrongful act should be reasonably connected to the duties assigned, even if it was performed in an unauthorized or improper way.

If these conditions are satisfied, courts generally hold the employer liable, even if they did not directly commit or endorse the wrongful act.

Master and Servant Relationship

Who is a Master and Who is a Servant?

In legal terminology, a “master” is someone who employs another person (a “servant”) to do work under his or her control. The servant is bound to follow the master’s instructions and performs tasks under direct supervision. This dynamic forms the bedrock of vicarious liability cases.

For example, a delivery driver working for a logistics company is considered a servant. The company is the master. If the driver negligently causes an accident while making deliveries, the company may be held vicariously liable.

Control Test and Other Determinants

The most common test used by courts to determine a master-servant relationship is the “control test”. This test examines whether the employer has the right to direct what the employee does and how they do it. The greater the control, the more likely the relationship fits the master-servant model.

Other relevant tests include:

- Integration Test: Whether the work done by the individual is integral to the employer’s business.

- Multiple/Economic Reality Test: Looks at various aspects, such as the source of payment, control, equipment ownership, etc.

No single test is definitive, but courts use them to analyze relationships on a case-by-case basis.

When is a Master Liable for the Acts of a Servant?

A master is liable for the acts of the servant only if the act was committed “in the course of employment.” This includes:

- Acts authorized by the master.

- Unauthorized acts closely connected with authorized duties.

- Negligent acts while performing job-related duties.

However, a master is not liable when the servant acts outside the scope of employment—commonly referred to as a “frolic of his own.” For instance, if a delivery driver deviates for personal reasons and causes harm, the company may not be liable.

Key Case Laws under Master-Servant Doctrine

- State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati (AIR 1962 SC 933)

A government vehicle driven negligently by a government employee caused a fatal accident. The court held the government vicariously liable for the wrongful act of its employee. - Limpus v. London General Omnibus Co. (1862)

A bus driver, despite explicit instructions, raced another bus and caused an accident. The company was held liable as the act was committed during employment. - Twine v. Beans Express Ltd. (1946)

A driver picked up unauthorized passengers, and an accident ensued. The court ruled against liability as the act was outside the scope of employment.

State Liability

Evolution of State Liability in Tort

In ancient times, the king could do no wrong. This principle led to sovereign immunity—a doctrine where the state was immune from legal action. However, modern democracies have evolved to recognize state liability, especially when public servants commit torts.

Indian jurisprudence, post-independence, gradually began to distinguish between sovereign and non-sovereign functions. The state cannot claim immunity in cases involving the latter.

Sovereign vs Non-Sovereign Functions

The doctrine of sovereign immunity has often been challenged, especially when it results in injustice. Indian courts have adopted the distinction between sovereign and non-sovereign functions to determine when the state can be held liable.

- Sovereign functions involve core government roles such as defense, foreign affairs, and lawmaking. In such cases, the state may not be held liable for the actions of its agents.

- Non-sovereign functions include commercial or administrative activities like maintaining roads, providing transportation, or managing hospitals. In these cases, the state can be vicariously liable.

This distinction was clearly drawn in cases like Kasturi Lal v. State of U.P. (AIR 1965 SC 1039), where the Supreme Court granted the state immunity because the tortious act occurred while performing a sovereign function (policing).

Leading Judicial Decisions

- State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati (1962)

This landmark decision marked a turning point. The Supreme Court held that the state was liable for the negligence of its employee who caused a fatal accident while driving a government vehicle. The Court ruled that driving a vehicle for official work is not a sovereign function. - Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa (1993)

A boy died in police custody. The Court emphasized state accountability and awarded compensation. It reaffirmed that fundamental rights violations could not be shielded by sovereign immunity. - Common Cause v. Union of India (1999)

The Court emphasized that the state is liable for torts committed by public servants while performing non-sovereign functions, especially where fundamental rights are infringed.

Case Law Illustrations

Here are a few more examples that illustrate how courts assess state liability:

| Case | Facts | Verdict |

| Basava Kom Dyamogouda v. State of Karnataka (1977) | Police lost seized gold ornaments. | Held: State liable for negligence. |

| Smt. Shyam Sunder v. State of Rajasthan (1974) | Accident caused by state-run transport bus. | Held: Vicarious liability applied. |

| Jay Laxmi Salt Works v. State of Gujarat (1994) | Salt works flooded due to breach in dam. | Held: State liable for negligence in non-sovereign function. |

These cases underscore that while the state may escape liability for actions under sovereign authority, it remains accountable for commercial, administrative, and public welfare activities.

Strict and Absolute Liability

What is Strict Liability?

Strict liability is a legal doctrine where a person is held liable for damage caused by their actions or property without the need to prove negligence or intent. This principle is typically applied in cases involving hazardous or dangerous activities.

The classic case that established this doctrine is Rylands v. Fletcher (1868). In this case, the defendant built a reservoir on his land, which burst and flooded the plaintiff’s coal mines. The Court ruled that anyone who brings something onto their land that is likely to cause harm if it escapes is strictly liable.

Key Elements of Strict Liability:

- Dangerous thing brought onto the land.

- Non-natural use of land.

- Escape of the harmful thing.

- Damage caused as a result.

The defendant is liable even if they took all reasonable care to prevent harm.

Exceptions to Strict Liability

However, there are some recognized exceptions:

- Plaintiff’s fault: If the damage was due to the plaintiff’s negligence.

- Act of God: Natural events like earthquakes.

- Act of a third party: If a third party, beyond the defendant’s control, caused the escape.

- Consent of the plaintiff: If the plaintiff consented to the danger.

- Statutory authority: If the activity was authorized by law.

These exceptions show that strict liability is not absolute in nature and that courts do allow certain defenses based on the circumstances.

Development of Absolute Liability in India

The concept of absolute liability was pioneered by Indian courts to address the limitations of strict liability. Unlike strict liability, absolute liability has no exceptions. It was developed to deal with the dangers posed by modern industrialization.

This doctrine was laid down in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987), following the Oleum gas leak in Delhi from a fertilizer plant operated by Shriram Foods and Fertilizers. The Supreme Court declared:

“An enterprise engaged in a hazardous or inherently dangerous activity owes an absolute and non-delegable duty to the community…”

The court emphasized that companies carrying out such activities must ensure that no harm is caused to anyone. If harm does occur, they are absolutely liable, regardless of precautions taken.

Relevant Cases (Rylands v Fletcher, MC Mehta v Union of India)

| Case | Jurisdiction | Principle Laid Down |

| Rylands v. Fletcher (1868) | UK | Introduced strict liability for escape of dangerous substances. |

| M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987) | India | Introduced absolute liability with no exceptions. |

| Indian Council for Enviro-Legal Action v. Union of India (1996) | India | Reiterated absolute liability for hazardous industries. |

These cases form the backbone of environmental tort law in India and provide a solid foundation for regulatory mechanisms in industrial operations.

Joint Tortfeasors

Definition and Legal Position

Joint tortfeasors are two or more persons who act together to commit a tort or whose independent acts combine to cause a single harm. Under this doctrine, all tortfeasors are jointly and severally liable, meaning the injured party can sue any one or all of them for full compensation.

For instance, if two doctors perform a negligent surgery together, and the patient suffers injury, both can be held liable as joint tortfeasors.

Principles Governing Joint Liability

The doctrine is governed by three main principles:

- Common design: Where tortfeasors act in concert.

- Concurrent negligence: Independent negligent acts that result in a single injury.

- Joint enterprise: Participants in a shared activity leading to harm.

Joint liability ensures that the injured party isn’t denied justice due to difficulty in proving who exactly caused the harm.

Contribution and Apportionment

In cases involving joint tortfeasors:

- The plaintiff may claim the entire damages from any one defendant.

- The defendant who pays can seek contribution from the other tortfeasors.

- Courts may apportion the liability based on degree of fault.

This mechanism promotes fairness by ensuring compensation to the injured while allowing internal adjustment among tortfeasors.

Landmark Judgments and Case Studies

- Koursk Case (1924)

Collision between two ships caused by combined negligence of both. Both parties held jointly liable. - Khushro S. Gandhi v. N.A. Guzdar (1970)

The Bombay High Court ruled that joint tortfeasors are jointly and severally liable, and contribution is permitted under equity principles. - Amrit Lal v. Government of India (1976)

The Court allowed recovery of full damages from the government, despite multiple parties being involved in a railway mishap.

These cases highlight how courts uphold the interests of justice by ensuring collective accountability.

Differences Between Vicarious, Strict, and Absolute Liability

Comparative Table

To understand the distinctions clearly, here’s a comparative table outlining the differences between vicarious, strict, and absolute liability:

| Feature | Vicarious Liability | Strict Liability | Absolute Liability |

| Basis | Relationship-based (e.g., master-servant) | Risk-based | Risk-based with zero exceptions |

| Fault | No personal fault required | No negligence needed | No negligence or exceptions |

| Defenses | Possible if the act was outside the scope of employment | Certain exceptions allowed (Act of God, third party, etc.) | No defense allowed |

| Liable Party | Master/employer or principal | Person who owns/dominates the hazardous activity | Owner of hazardous activity or enterprise |

| Origin | Common law principle | Originated from Rylands v. Fletcher | Developed by Indian judiciary |

| Example Case | State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati | Rylands v. Fletcher | M.C. Mehta v. Union of India |

Applicability in Modern Law

All three forms of liability play critical roles in modern legal systems but differ significantly in scope and applicability.

- Vicarious liability is most prevalent in employment contexts and public authority accountability. It ensures that institutions, whether public or private, do not escape responsibility for the actions of those under their control.

- Strict liability applies primarily to situations involving dangerous substances or conditions—like chemicals, explosives, or large-scale machinery.

- Absolute liability, particularly in India, is used in environmental and industrial disasters. Given the growing risks associated with industrialization and pollution, this doctrine has become a cornerstone of environmental justice.

These doctrines aren’t mutually exclusive but are used in tandem depending on the nature of the harm and the relationship between the parties involved.

Vicarious Liability in Modern Context

Employer’s Liability in Gig Economy

The rise of the gig economy has introduced a new challenge to traditional vicarious liability principles. Companies like Uber, Swiggy, and Zomato claim that their workers are independent contractors, not employees, to avoid liability for their actions. This classification is under scrutiny globally.

However, courts are increasingly considering the control and economic dependency that gig workers have on platforms. For example:

- In the UK, Uber drivers were declared “workers,” not independent contractors, giving them protection and imposing responsibilities on Uber.

- In India, although the judiciary has yet to deliver landmark rulings, consumer complaints and labor disputes are pushing for reclassification.

The key legal question is: Does the company have sufficient control over the individual’s work? If yes, vicarious liability may still apply.

Vicarious Liability in Cyber Law

In the digital age, liability extends to online platforms and service providers. Social media giants, internet service providers, and website hosts may be held vicariously liable for the content posted by users, especially if:

- They fail to remove illegal or harmful content after being notified.

- Their platform design or algorithms amplify such content.

Example: If a user uploads defamatory content on a platform and the company doesn’t act after being informed, it may face vicarious liability for allowing harm to persist.

Some countries now have clear legislation on intermediary liability, while others are relying on judicial interpretation.

State and Police Misconduct

Vicarious liability is increasingly being invoked in cases of police brutality and custodial deaths. Though the state may try to shield itself under sovereign immunity, courts are piercing that veil, especially when constitutional rights are violated.

For instance, in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997), the Supreme Court laid down guidelines for arrest and detention to prevent custodial abuse. Any violation can now attract both personal and vicarious liability against the police force and the state.

Modern vicarious liability thus stretches far beyond employment—it is now a key tool for ensuring institutional accountability in a wide variety of settings.

Case Studies and Practical Examples

Indian Case Examples

- M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Oleum Gas Leak Case)

The Supreme Court imposed absolute liability on the industry, departing from the rule in Rylands v. Fletcher and emphasizing the need for a higher standard in the context of industrial activities. - Vidhyawati Case (1962)

Government held liable for the negligence of a state-employed driver, marking a milestone in state liability under non-sovereign functions. - Kasturi Lal v. State of UP (1965)

In this case, the state was held not liable due to the act being under a sovereign function (policing). The court distinguished it from cases involving non-sovereign functions. - Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa (1993)

Compensation was awarded for custodial death. The court ruled that the state cannot claim immunity when fundamental rights are breached. - Indian Medical Association v. V.P. Shantha (1995)

Doctors and hospitals were held liable under consumer protection laws, clarifying how institutions can face vicarious liability for medical negligence.

International Case Examples

- Lister v. Hesley Hall Ltd. (UK, 2001)

A school was held vicariously liable for sexual abuse committed by a warden. The court emphasized the “close connection” between the employee’s role and the wrongful act. - Bazley v. Curry (Canada, 1999)

A non-profit organization was found liable for abuse committed by its employee in a children’s home. The court underlined the need to provide justice to victims even when the wrongdoer was a single individual. - Majrowski v. Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust (UK, 2006)

The NHS Trust was held vicariously liable for harassment committed by an employee, extending liability under the Protection from Harassment Act.

These real-world examples show the extensive and evolving application of vicarious, strict, and absolute liability across various sectors and legal systems.

Conclusion

Vicarious liability, along with its cousins—strict and absolute liability—plays an essential role in shaping modern tort law. These doctrines are not merely legal constructs; they are tools of social justice, accountability, and deterrence. Whether it’s an employer, the state, or a corporation, the law ensures that no one can hide behind hierarchy or structure to escape responsibility.

In a world where complex organizational structures and technologies often shield the actual wrongdoer, these liability doctrines ensure that the victim is not left without remedy. From master-servant relationships to state negligence and industrial disasters, the principle continues to evolve and adapt to new societal challenges.

It’s vital that courts and lawmakers continue to uphold and refine these principles to ensure justice is both accessible and effective in today’s dynamic legal landscape.

FAQs

1. What is the main purpose of vicarious liability?

The main purpose is to ensure that victims receive compensation from someone who has the financial capacity and control to prevent the wrongdoing, usually the employer or the state.

2. Can an independent contractor create vicarious liability?

Generally, no. Vicarious liability typically applies to employees, not independent contractors, unless the contractor was treated as an employee based on control or integration.

3. How does vicarious liability affect employers?

Employers must ensure proper training, supervision, and background checks of employees because they can be held liable for wrongful acts committed by employees during employment.

4. Is strict liability applicable in criminal law?

Strict liability does exist in criminal law, particularly in regulatory offences (like environmental violations), where intent or knowledge isn’t required to prove guilt.

5. How is state liability different from master-servant liability?

State liability involves government responsibility for wrongful acts of public servants, often limited by sovereign immunity. Master-servant liability pertains to private relationships and does not generally benefit from such immunity.