Introduction to Punishment

Understanding the Concept of Punishment

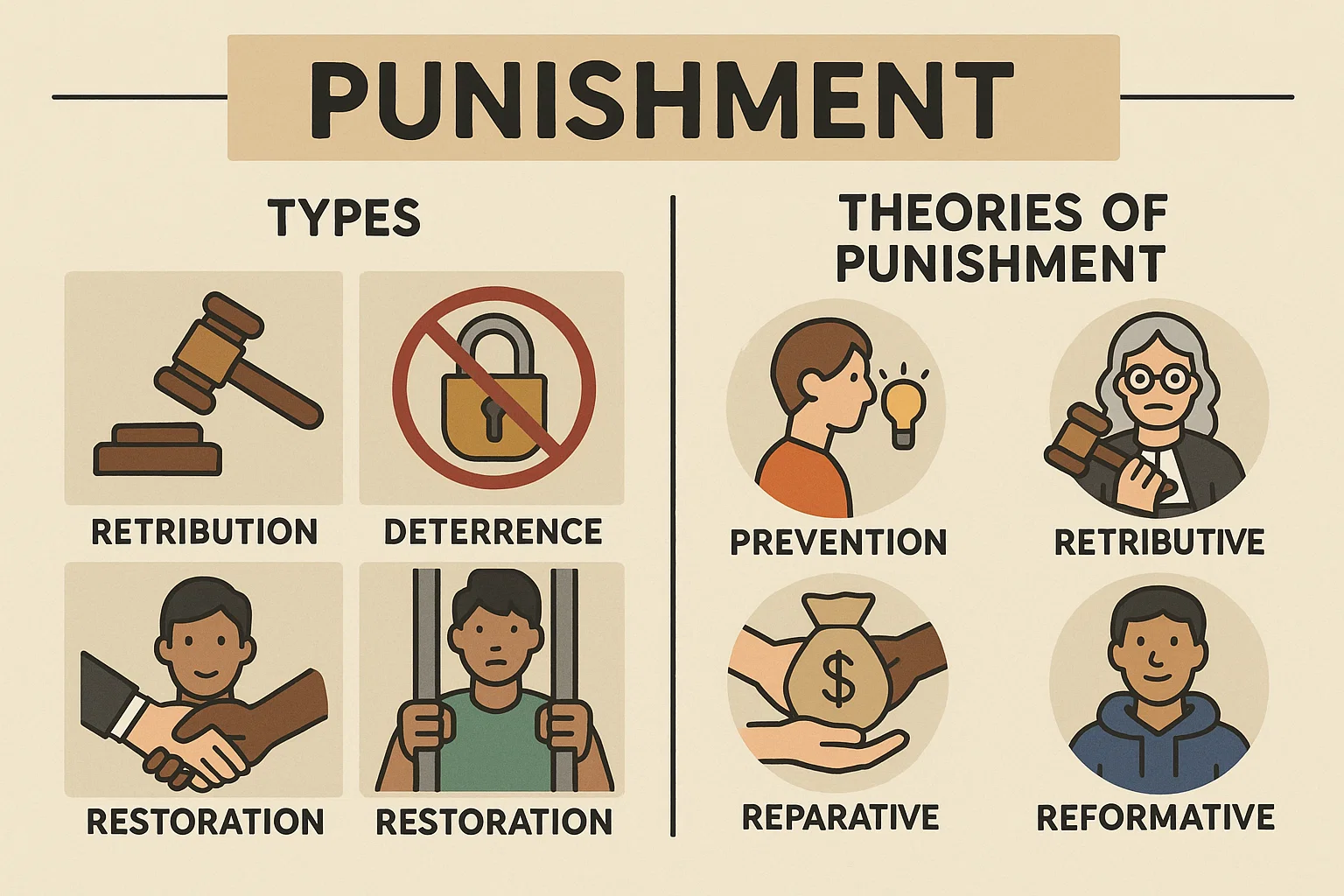

Punishment is one of the oldest and most controversial aspects of human civilization. From the dawn of society, people have used punishment as a means of maintaining order, enforcing norms, and dealing with those who violate laws or expectations. But what really is punishment? At its core, punishment is the deliberate infliction of pain or deprivation in response to wrongdoing. It’s society’s way of signaling that certain behaviors are unacceptable and come with consequences.

Punishment isn’t just about revenge or causing harm. It’s a structured response, governed by legal systems and informed by centuries of ethical, moral, and philosophical debate. Whether it’s a parent grounding a child or a judge sentencing a criminal to prison, punishment reflects the values, fears, and hopes of the people administering it.

In modern contexts, punishment takes on many forms—from fines and jail time to community service or even capital punishment. But while the forms may change, the purpose remains consistent: to deter, correct, or isolate the wrongdoer. Understanding punishment requires diving into the various types and the theories that justify them, which helps explain why we punish and how we might do it better.

Historical Evolution of Punishment in Human Societies

The way societies punish has evolved dramatically over time. In ancient civilizations like Babylon, punishment was brutally retributive—think of the famous phrase “an eye for an eye.” Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all practiced forms of punishment that were often public, painful, and deeply symbolic. These punishments were designed to humiliate the offender while warning others not to follow the same path.

Medieval Europe continued this trend with practices like beheading, drawing and quartering, and public whippings. Religion played a huge role, and many punishments were linked to sin and morality, not just legal codes. However, the Enlightenment era marked a turning point. Thinkers like Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham began to question the effectiveness and ethics of harsh punishment, advocating instead for proportionate, fair, and rational responses to crime.

The industrial era saw the rise of prisons as the main form of punishment. Institutions were built not just to detain but to reform. Fast forward to today, and many countries are experimenting with restorative justice, rehabilitation programs, and alternatives to incarceration. Our evolving understanding of human psychology, inequality, and social justice continues to shape how punishment is used.

Purpose of Punishment

Why Societies Use Punishment

Why do we punish people? At first glance, it might seem simple: someone does wrong, they get punished. But the reality is far more complex. Societies punish to maintain order, reinforce norms, and promote justice. When someone commits a crime or violates a rule, failing to act sends a dangerous message—that actions have no consequences. Punishment fills that gap, sending a clear signal that behavior has boundaries.

Another key reason is deterrence. By punishing one person, society hopes to discourage others from committing similar acts. Then there’s protection: sometimes the aim is to physically prevent a dangerous person from harming others, which is why imprisonment exists. Punishment also serves as a form of reparation, making the offender “pay” in some way for their wrongs.

In many systems, punishment also aims to rehabilitate. That means helping offenders understand the harm they’ve caused and giving them tools to change. From mandatory therapy sessions to educational programs in prisons, modern punishment often looks to the future, not just the past. It’s about transforming rather than just tormenting.

Social, Moral, and Legal Objectives of Punishment

Punishment serves not just a practical purpose, but also fulfills important social and moral roles. Legally, it affirms the rule of law—ensuring that laws mean something and that no one is above them. Socially, it maintains public confidence in the justice system. Imagine a society where theft, assault, or fraud went unpunished. People would feel unsafe and lose trust in authorities.

Morally, punishment communicates values. It tells the community that certain behaviors are unacceptable and that justice matters. In a way, every punishment is a statement: “We, as a society, do not tolerate this.” That’s why public reaction is often so strong when punishments are seen as too lenient or too harsh.

At the same time, modern legal systems also emphasize proportionality—ensuring the punishment fits the crime—and fairness. These principles are rooted in both ethics and practicality. Overly harsh punishments can backfire, leading to resentment, recidivism, or social unrest. On the flip side, weak punishment can embolden wrongdoers. The goal is to strike a delicate balance between deterrence, justice, and mercy.

Types of Punishment

Capital Punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the most extreme form of punishment. It involves executing a person as retribution for a particularly severe crime—usually murder or crimes against the state like terrorism or treason. It’s one of the oldest types of punishment, dating back to ancient civilizations that used beheading, hanging, or burning as forms of state-sanctioned killing.

Today, capital punishment remains a controversial topic. Supporters argue that it delivers ultimate justice, serves as a strong deterrent, and offers closure to victims’ families. They claim that some crimes are so heinous that only death is an appropriate response.

Opponents, however, see capital punishment as inhumane, irreversible, and prone to error. There’s the ever-present risk of wrongful conviction—where innocent people could be executed due to flawed investigations, racial bias, or prosecutorial misconduct. There’s also the ethical debate: does the state have the moral authority to take a life, even if the person is guilty?

Methods of capital punishment vary by country and era. Lethal injection is the most common modern method, considered “humane” by supporters. Other methods—like firing squads, hanging, or electrocution—are still used in some parts of the world. In contrast, over 70% of countries worldwide have either abolished or stopped using the death penalty in practice, reflecting a global shift toward more rehabilitative approaches.

Capital punishment raises fundamental questions about justice, humanity, and the purpose of punishment itself. Is it justice or revenge? Deterrence or destruction? These questions remain fiercely debated in courts, governments, and society.

Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment refers to physical penalties inflicted on the body of an offender. Historically, this was one of the most common forms of punishment—flogging, whipping, branding, and even mutilation were widely practiced. These punishments were often carried out in public to maximize their deterrent effect and reinforce societal norms through fear and shame.

In ancient and medieval societies, corporal punishment was a way to deliver swift justice. It required fewer resources than imprisonment and left a lasting physical and psychological impact on the offender. However, with the rise of modern human rights ideologies, the use of corporal punishment in legal systems has drastically declined.

Today, corporal punishment is considered a violation of human dignity by many international human rights organizations. Most modern legal systems have outlawed its use in criminal justice settings, although it persists in some parts of the world, especially in countries governed by strict religious laws or authoritarian regimes.

There’s still an ongoing debate about corporal punishment, especially in schools and domestic settings. While some argue it’s a necessary disciplinary tool, others highlight its long-term psychological harms, including trauma, aggression, and impaired emotional development.

The move away from corporal punishment reflects a broader societal shift toward more humane and rehabilitative justice systems. The focus has shifted from inflicting pain to correcting behavior and addressing root causes of crime.

Imprisonment

Imprisonment is currently the most widespread form of criminal punishment across the globe. It involves confining individuals in jails or prisons for a specified period as a consequence of violating the law. Its primary purposes include isolating offenders from society, deterring future crimes, reforming criminal behavior, and, to some extent, providing retributive justice.

There are various types of imprisonment:

- Short-term sentences for minor offenses like petty theft or vandalism.

- Long-term sentences for more serious crimes such as armed robbery, homicide, or large-scale fraud.

- Life imprisonment for heinous crimes without the possibility of parole.

- Solitary confinement, a controversial form used as punishment within prison, which isolates the inmate entirely from others.

While prisons are designed to maintain order and rehabilitate, in practice, many face criticism for failing to do so. Overcrowding, violence, gang activity, and poor living conditions often turn prisons into breeding grounds for more crime rather than centers of reform.

One of the biggest concerns in the modern prison system is recidivism—the tendency for released prisoners to re-offend. High recidivism rates in many countries suggest that imprisonment alone isn’t always effective at deterring crime or rehabilitating offenders.

Moreover, the prison-industrial complex—especially in privatized systems—has drawn attention to how economic incentives can influence incarceration rates, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. Calls for prison reform emphasize rehabilitation, education, and restorative justice as better long-term solutions.

Fines and Monetary Penalties

Fines are financial punishments imposed on individuals or organizations for violating laws or regulations. They’re among the most commonly used forms of punishment, especially for minor infractions like traffic violations, public disorder, or corporate misconduct.

One of the main advantages of fines is their flexibility and efficiency. They don’t require incarceration or significant state resources. Instead, they impose a direct economic cost on the offender, theoretically deterring future infractions. Courts often determine fines based on the severity of the offense, and in some cases, the financial capacity of the offender.

However, fines are not without criticism. A major issue is the disproportionate impact on low-income individuals. For the wealthy, a fine might be a minor inconvenience. For someone living paycheck to paycheck, it can be devastating, potentially leading to a cycle of debt, missed payments, and even jail time in extreme cases.

In contrast, some justice systems have adopted day-fine models, where fines are proportionate to the offender’s income. This makes the punishment more equitable, ensuring that it “hurts” equally across income levels.

For corporations, fines are often used as a regulatory tool. Environmental violations, false advertising, or worker safety breaches might be punished with hefty monetary penalties. But again, critics argue that for large companies, fines are just another business expense unless they’re large enough to influence behavior.

Used effectively, fines can serve as a quick and fair way to address minor wrongdoing. But their effectiveness and fairness depend heavily on how they’re structured and enforced.

Community Service

Community service is a form of punishment that requires offenders to perform unpaid work for the benefit of the community. It’s often used as an alternative to jail time, especially for non-violent offenders, juveniles, or first-time lawbreakers. The idea is to make amends by giving back, rather than simply suffering a penalty.

Common examples of community service include:

- Cleaning public parks or streets

- Volunteering in shelters or community centers

- Helping in public libraries or food banks

- Participating in environmental cleanup projects

Community service aims to achieve multiple goals. It holds offenders accountable, teaches responsibility, and allows them to maintain ties to society—potentially reducing the risk of reoffending. It’s also far more cost-effective than incarceration, easing the burden on overcrowded prison systems.

One of the key benefits of community service is that it balances punishment with rehabilitation. Offenders often gain valuable skills, develop empathy, and reconnect with community values. It can be a powerful tool for reintegration and personal growth.

However, like any system, it has challenges. Sometimes the work assigned is repetitive or lacks meaningful engagement. There’s also the risk of inequity if community service is disproportionately used for certain groups while others face harsher penalties.

When implemented properly, community service offers a restorative approach that emphasizes healing over harm—a modern reflection of justice with a human touch.

Probation and Parole

Probation and parole are alternatives to traditional incarceration that allow offenders to remain in the community under specific conditions. They are often confused but serve different roles in the justice system.

- Probation is a court-ordered period of supervision in the community, typically given instead of prison time. Offenders must follow strict rules, such as attending counseling, avoiding certain people or places, and staying drug-free.

- Parole, on the other hand, is granted after an offender has served part of their prison sentence. It allows for early release but comes with similar conditions and close monitoring.

Both systems are grounded in the belief that not all offenders need to be locked away. Some can be safely managed in society, especially with support and supervision. Probation and parole officers play a crucial role, acting as both monitors and mentors—ensuring compliance while encouraging reform.

However, these systems are not without problems. Technical violations—like missing a meeting or failing a drug test—can send individuals back to prison, even if they haven’t committed a new crime. This contributes to the “revolving door” problem in criminal justice.

Supporters argue that probation and parole reduce prison overcrowding and save public money. But to be effective, these systems need robust infrastructure, counseling services, and fair enforcement. Done right, they can be powerful tools for second chances; done wrong, they can be traps that pull people deeper into the justice system.

Theories of Punishment

Retributive Theory of Punishment

Retribution is probably the oldest and most emotionally resonant theory of punishment. At its core, retributive theory holds that punishment is justified because the offender deserves it. It’s about moral balance—restoring a sense of justice that was disturbed when a crime was committed.

This theory is deeply tied to the idea of “just deserts.” That means the punishment should fit the crime, and it should be proportional. If someone steals, they should be punished for theft—not tortured or humiliated. Retribution isn’t about revenge; it’s about fairness. The wrongdoer must “pay” for their actions, not to deter others, but because it’s the right thing to do.

What sets retributive theory apart is that it doesn’t care whether punishment deters future crime or rehabilitates the offender. Its only concern is justice. Critics argue that this approach can be too rigid or vengeful, ignoring context like poverty, trauma, or mental health. Still, it remains a powerful force in many legal systems and public attitudes.

Deterrent Theory of Punishment

The deterrent theory is all about sending a message—not just to the individual who committed the crime, but to society at large. According to this theory, punishment should be severe enough to discourage people from engaging in unlawful behavior. If people fear the consequences, the logic goes, they’ll think twice before breaking the law.

There are two key forms of deterrence: general deterrence and specific deterrence. General deterrence targets the public. When someone is punished publicly or severely, it acts as a warning to others: “Don’t do this, or this could happen to you.” Think of publicized court cases or harsh penalties for crimes like drug trafficking—these are meant to scare others into obedience.

Specific deterrence, on the other hand, is aimed directly at the offender. The goal here is to make sure the person who committed the crime doesn’t do it again. The idea is that after experiencing the consequences firsthand—be it a fine, imprisonment, or some other penalty—the offender will avoid similar actions in the future.

While the deterrent theory seems logical, critics often question its real-world effectiveness. Does the death penalty actually stop people from committing murder? Do long prison sentences truly deter repeat offenders? Studies have shown mixed results, suggesting that fear alone may not be enough to prevent crime—especially when social, economic, and psychological factors are at play.

Reformative Theory of Punishment

If retribution is about justice and deterrence is about fear, then the reformative theory is about change. Reformative punishment focuses on helping the offender understand their mistake and transform into a better, law-abiding person. This theory views crime not just as a moral failure, but often as a symptom of deeper issues—poverty, lack of education, trauma, addiction, or mental illness.

Under this approach, the goal isn’t to make the criminal suffer, but to rehabilitate them. This might involve therapy, education, skill-building, counseling, or substance abuse treatment. The hope is that, with the right support, offenders can reintegrate into society as productive citizens.

This theory is especially popular in modern legal systems that emphasize restorative and humane approaches to justice. Scandinavian countries, for example, have famously adopted reformative principles—using open prisons and focusing on offender welfare rather than punitive conditions.

Of course, reformative theory has its critics. Some argue that it can be too soft on crime, potentially undermining justice or failing to satisfy victims. Others worry about fairness—why should someone who commits a crime get access to resources that law-abiding citizens might not? But overall, reformative punishment reflects a progressive view that believes in second chances and the potential for human growth.

Preventive Theory of Punishment

The preventive theory of punishment is based on a very simple idea: if someone is physically incapable of committing a crime, then they won’t be able to break the law again. This theory doesn’t focus on moral deserts or personal reform. Instead, it’s all about protecting society by removing or restricting the offender’s freedom.

The most common form of preventive punishment is imprisonment. By locking someone up, the justice system effectively removes them from society—at least temporarily. In extreme cases, this theory also justifies life imprisonment or even capital punishment, under the logic that permanent removal is the surest form of prevention.

This theory plays a significant role in handling dangerous or repeat offenders. When someone has shown that they are a persistent threat to others, the focus shifts from rehabilitation or deterrence to straightforward prevention. The idea is that protecting innocent people justifies severe restrictions on the offender’s liberty.

Preventive punishment is also applied through mechanisms like restraining orders, electronic ankle monitors, or long-term surveillance. These don’t always involve prison but still aim to prevent future crimes by controlling the offender’s actions.

Still, this approach raises ethical and legal concerns. Should people be punished for crimes they might commit in the future? Does it violate basic human rights to incarcerate someone for being a “risk”? These are ongoing debates, especially in cases involving terrorism, chronic sexual offenders, or individuals with untreated mental illness.

Conclusion:

Punishment plays a crucial role in maintaining law, order, and social harmony within a society. It serves not only as a deterrent to crime but also as a means of reforming offenders, delivering justice, and upholding moral and legal standards. The various types of punishment—such as capital punishment, imprisonment, fines, and community service—are applied based on the nature and gravity of the offense.

The theories of punishment, including retributive, deterrent, reformative, preventive, and expiatory theories, provide different philosophical and practical approaches to justify and implement punishment. While the retributive theory emphasizes moral vengeance, the reformative theory focuses on transforming offenders into law-abiding citizens. Each theory contributes uniquely to the legal framework, often overlapping in modern judicial systems.

A balanced and just system of punishment, guided by a blend of these theories, is essential for safeguarding society, promoting justice, and ensuring that punishment leads to positive outcomes for both individuals and the community at large.

Punishment, Types and Theories of Punishment

Introduction to Punishment

Understanding the Concept of Punishment

Punishment is one of the oldest and most controversial aspects of human civilization. From the dawn of society, people have used punishment as a means of maintaining order, enforcing norms, and dealing with those who violate laws or expectations. But what really is punishment? At its core, punishment is the deliberate infliction of pain or deprivation in response to wrongdoing. It’s society’s way of signaling that certain behaviors are unacceptable and come with consequences.

Punishment isn’t just about revenge or causing harm. It’s a structured response, governed by legal systems and informed by centuries of ethical, moral, and philosophical debate. Whether it’s a parent grounding a child or a judge sentencing a criminal to prison, punishment reflects the values, fears, and hopes of the people administering it.

In modern contexts, punishment takes on many forms—from fines and jail time to community service or even capital punishment. But while the forms may change, the purpose remains consistent: to deter, correct, or isolate the wrongdoer. Understanding punishment requires diving into the various types and the theories that justify them, which helps explain why we punish and how we might do it better.

Historical Evolution of Punishment in Human Societies

The way societies punish has evolved dramatically over time. In ancient civilizations like Babylon, punishment was brutally retributive—think of the famous phrase “an eye for an eye.” Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all practiced forms of punishment that were often public, painful, and deeply symbolic. These punishments were designed to humiliate the offender while warning others not to follow the same path.

Medieval Europe continued this trend with practices like beheading, drawing and quartering, and public whippings. Religion played a huge role, and many punishments were linked to sin and morality, not just legal codes. However, the Enlightenment era marked a turning point. Thinkers like Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham began to question the effectiveness and ethics of harsh punishment, advocating instead for proportionate, fair, and rational responses to crime.

The industrial era saw the rise of prisons as the main form of punishment. Institutions were built not just to detain but to reform. Fast forward to today, and many countries are experimenting with restorative justice, rehabilitation programs, and alternatives to incarceration. Our evolving understanding of human psychology, inequality, and social justice continues to shape how punishment is used.

Purpose of Punishment

Why Societies Use Punishment

Why do we punish people? At first glance, it might seem simple: someone does wrong, they get punished. But the reality is far more complex. Societies punish to maintain order, reinforce norms, and promote justice. When someone commits a crime or violates a rule, failing to act sends a dangerous message—that actions have no consequences. Punishment fills that gap, sending a clear signal that behavior has boundaries.

Another key reason is deterrence. By punishing one person, society hopes to discourage others from committing similar acts. Then there’s protection: sometimes the aim is to physically prevent a dangerous person from harming others, which is why imprisonment exists. Punishment also serves as a form of reparation, making the offender “pay” in some way for their wrongs.

In many systems, punishment also aims to rehabilitate. That means helping offenders understand the harm they’ve caused and giving them tools to change. From mandatory therapy sessions to educational programs in prisons, modern punishment often looks to the future, not just the past. It’s about transforming rather than just tormenting.

Social, Moral, and Legal Objectives of Punishment

Punishment serves not just a practical purpose, but also fulfills important social and moral roles. Legally, it affirms the rule of law—ensuring that laws mean something and that no one is above them. Socially, it maintains public confidence in the justice system. Imagine a society where theft, assault, or fraud went unpunished. People would feel unsafe and lose trust in authorities.

Morally, punishment communicates values. It tells the community that certain behaviors are unacceptable and that justice matters. In a way, every punishment is a statement: “We, as a society, do not tolerate this.” That’s why public reaction is often so strong when punishments are seen as too lenient or too harsh.

At the same time, modern legal systems also emphasize proportionality—ensuring the punishment fits the crime—and fairness. These principles are rooted in both ethics and practicality. Overly harsh punishments can backfire, leading to resentment, recidivism, or social unrest. On the flip side, weak punishment can embolden wrongdoers. The goal is to strike a delicate balance between deterrence, justice, and mercy.

Types of Punishment

Capital Punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the most extreme form of punishment. It involves executing a person as retribution for a particularly severe crime—usually murder or crimes against the state like terrorism or treason. It’s one of the oldest types of punishment, dating back to ancient civilizations that used beheading, hanging, or burning as forms of state-sanctioned killing.

Today, capital punishment remains a controversial topic. Supporters argue that it delivers ultimate justice, serves as a strong deterrent, and offers closure to victims’ families. They claim that some crimes are so heinous that only death is an appropriate response.

Opponents, however, see capital punishment as inhumane, irreversible, and prone to error. There’s the ever-present risk of wrongful conviction—where innocent people could be executed due to flawed investigations, racial bias, or prosecutorial misconduct. There’s also the ethical debate: does the state have the moral authority to take a life, even if the person is guilty?

Methods of capital punishment vary by country and era. Lethal injection is the most common modern method, considered “humane” by supporters. Other methods—like firing squads, hanging, or electrocution—are still used in some parts of the world. In contrast, over 70% of countries worldwide have either abolished or stopped using the death penalty in practice, reflecting a global shift toward more rehabilitative approaches.

Capital punishment raises fundamental questions about justice, humanity, and the purpose of punishment itself. Is it justice or revenge? Deterrence or destruction? These questions remain fiercely debated in courts, governments, and society.

Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment refers to physical penalties inflicted on the body of an offender. Historically, this was one of the most common forms of punishment—flogging, whipping, branding, and even mutilation were widely practiced. These punishments were often carried out in public to maximize their deterrent effect and reinforce societal norms through fear and shame.

In ancient and medieval societies, corporal punishment was a way to deliver swift justice. It required fewer resources than imprisonment and left a lasting physical and psychological impact on the offender. However, with the rise of modern human rights ideologies, the use of corporal punishment in legal systems has drastically declined.

Today, corporal punishment is considered a violation of human dignity by many international human rights organizations. Most modern legal systems have outlawed its use in criminal justice settings, although it persists in some parts of the world, especially in countries governed by strict religious laws or authoritarian regimes.

There’s still an ongoing debate about corporal punishment, especially in schools and domestic settings. While some argue it’s a necessary disciplinary tool, others highlight its long-term psychological harms, including trauma, aggression, and impaired emotional development.

The move away from corporal punishment reflects a broader societal shift toward more humane and rehabilitative justice systems. The focus has shifted from inflicting pain to correcting behavior and addressing root causes of crime.

Imprisonment

Imprisonment is currently the most widespread form of criminal punishment across the globe. It involves confining individuals in jails or prisons for a specified period as a consequence of violating the law. Its primary purposes include isolating offenders from society, deterring future crimes, reforming criminal behavior, and, to some extent, providing retributive justice.

There are various types of imprisonment:

- Short-term sentences for minor offenses like petty theft or vandalism.

- Long-term sentences for more serious crimes such as armed robbery, homicide, or large-scale fraud.

- Life imprisonment for heinous crimes without the possibility of parole.

- Solitary confinement, a controversial form used as punishment within prison, which isolates the inmate entirely from others.

While prisons are designed to maintain order and rehabilitate, in practice, many face criticism for failing to do so. Overcrowding, violence, gang activity, and poor living conditions often turn prisons into breeding grounds for more crime rather than centers of reform.

One of the biggest concerns in the modern prison system is recidivism—the tendency for released prisoners to re-offend. High recidivism rates in many countries suggest that imprisonment alone isn’t always effective at deterring crime or rehabilitating offenders.

Moreover, the prison-industrial complex—especially in privatized systems—has drawn attention to how economic incentives can influence incarceration rates, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. Calls for prison reform emphasize rehabilitation, education, and restorative justice as better long-term solutions.

Fines and Monetary Penalties

Fines are financial punishments imposed on individuals or organizations for violating laws or regulations. They’re among the most commonly used forms of punishment, especially for minor infractions like traffic violations, public disorder, or corporate misconduct.

One of the main advantages of fines is their flexibility and efficiency. They don’t require incarceration or significant state resources. Instead, they impose a direct economic cost on the offender, theoretically deterring future infractions. Courts often determine fines based on the severity of the offense, and in some cases, the financial capacity of the offender.

However, fines are not without criticism. A major issue is the disproportionate impact on low-income individuals. For the wealthy, a fine might be a minor inconvenience. For someone living paycheck to paycheck, it can be devastating, potentially leading to a cycle of debt, missed payments, and even jail time in extreme cases.

In contrast, some justice systems have adopted day-fine models, where fines are proportionate to the offender’s income. This makes the punishment more equitable, ensuring that it “hurts” equally across income levels.

For corporations, fines are often used as a regulatory tool. Environmental violations, false advertising, or worker safety breaches might be punished with hefty monetary penalties. But again, critics argue that for large companies, fines are just another business expense unless they’re large enough to influence behavior.

Used effectively, fines can serve as a quick and fair way to address minor wrongdoing. But their effectiveness and fairness depend heavily on how they’re structured and enforced.

Community Service

Community service is a form of punishment that requires offenders to perform unpaid work for the benefit of the community. It’s often used as an alternative to jail time, especially for non-violent offenders, juveniles, or first-time lawbreakers. The idea is to make amends by giving back, rather than simply suffering a penalty.

Common examples of community service include:

- Cleaning public parks or streets

- Volunteering in shelters or community centers

- Helping in public libraries or food banks

- Participating in environmental cleanup projects

Community service aims to achieve multiple goals. It holds offenders accountable, teaches responsibility, and allows them to maintain ties to society—potentially reducing the risk of reoffending. It’s also far more cost-effective than incarceration, easing the burden on overcrowded prison systems.

One of the key benefits of community service is that it balances punishment with rehabilitation. Offenders often gain valuable skills, develop empathy, and reconnect with community values. It can be a powerful tool for reintegration and personal growth.

However, like any system, it has challenges. Sometimes the work assigned is repetitive or lacks meaningful engagement. There’s also the risk of inequity if community service is disproportionately used for certain groups while others face harsher penalties.

When implemented properly, community service offers a restorative approach that emphasizes healing over harm—a modern reflection of justice with a human touch.

Probation and Parole

Probation and parole are alternatives to traditional incarceration that allow offenders to remain in the community under specific conditions. They are often confused but serve different roles in the justice system.

- Probation is a court-ordered period of supervision in the community, typically given instead of prison time. Offenders must follow strict rules, such as attending counseling, avoiding certain people or places, and staying drug-free.

- Parole, on the other hand, is granted after an offender has served part of their prison sentence. It allows for early release but comes with similar conditions and close monitoring.

Both systems are grounded in the belief that not all offenders need to be locked away. Some can be safely managed in society, especially with support and supervision. Probation and parole officers play a crucial role, acting as both monitors and mentors—ensuring compliance while encouraging reform.

However, these systems are not without problems. Technical violations—like missing a meeting or failing a drug test—can send individuals back to prison, even if they haven’t committed a new crime. This contributes to the “revolving door” problem in criminal justice.

Supporters argue that probation and parole reduce prison overcrowding and save public money. But to be effective, these systems need robust infrastructure, counseling services, and fair enforcement. Done right, they can be powerful tools for second chances; done wrong, they can be traps that pull people deeper into the justice system.

Theories of Punishment

Retributive Theory of Punishment

Retribution is probably the oldest and most emotionally resonant theory of punishment. At its core, retributive theory holds that punishment is justified because the offender deserves it. It’s about moral balance—restoring a sense of justice that was disturbed when a crime was committed.

This theory is deeply tied to the idea of “just deserts.” That means the punishment should fit the crime, and it should be proportional. If someone steals, they should be punished for theft—not tortured or humiliated. Retribution isn’t about revenge; it’s about fairness. The wrongdoer must “pay” for their actions, not to deter others, but because it’s the right thing to do.

What sets retributive theory apart is that it doesn’t care whether punishment deters future crime or rehabilitates the offender. Its only concern is justice. Critics argue that this approach can be too rigid or vengeful, ignoring context like poverty, trauma, or mental health. Still, it remains a powerful force in many legal systems and public attitudes.

Deterrent Theory of Punishment

The deterrent theory is all about sending a message—not just to the individual who committed the crime, but to society at large. According to this theory, punishment should be severe enough to discourage people from engaging in unlawful behavior. If people fear the consequences, the logic goes, they’ll think twice before breaking the law.

There are two key forms of deterrence: general deterrence and specific deterrence. General deterrence targets the public. When someone is punished publicly or severely, it acts as a warning to others: “Don’t do this, or this could happen to you.” Think of publicized court cases or harsh penalties for crimes like drug trafficking—these are meant to scare others into obedience.

Specific deterrence, on the other hand, is aimed directly at the offender. The goal here is to make sure the person who committed the crime doesn’t do it again. The idea is that after experiencing the consequences firsthand—be it a fine, imprisonment, or some other penalty—the offender will avoid similar actions in the future.

While the deterrent theory seems logical, critics often question its real-world effectiveness. Does the death penalty actually stop people from committing murder? Do long prison sentences truly deter repeat offenders? Studies have shown mixed results, suggesting that fear alone may not be enough to prevent crime—especially when social, economic, and psychological factors are at play.

Reformative Theory of Punishment

If retribution is about justice and deterrence is about fear, then the reformative theory is about change. Reformative punishment focuses on helping the offender understand their mistake and transform into a better, law-abiding person. This theory views crime not just as a moral failure, but often as a symptom of deeper issues—poverty, lack of education, trauma, addiction, or mental illness.

Under this approach, the goal isn’t to make the criminal suffer, but to rehabilitate them. This might involve therapy, education, skill-building, counseling, or substance abuse treatment. The hope is that, with the right support, offenders can reintegrate into society as productive citizens.

This theory is especially popular in modern legal systems that emphasize restorative and humane approaches to justice. Scandinavian countries, for example, have famously adopted reformative principles—using open prisons and focusing on offender welfare rather than punitive conditions.

Of course, reformative theory has its critics. Some argue that it can be too soft on crime, potentially undermining justice or failing to satisfy victims. Others worry about fairness—why should someone who commits a crime get access to resources that law-abiding citizens might not? But overall, reformative punishment reflects a progressive view that believes in second chances and the potential for human growth.

Preventive Theory of Punishment

The preventive theory of punishment is based on a very simple idea: if someone is physically incapable of committing a crime, then they won’t be able to break the law again. This theory doesn’t focus on moral deserts or personal reform. Instead, it’s all about protecting society by removing or restricting the offender’s freedom.

The most common form of preventive punishment is imprisonment. By locking someone up, the justice system effectively removes them from society—at least temporarily. In extreme cases, this theory also justifies life imprisonment or even capital punishment, under the logic that permanent removal is the surest form of prevention.

This theory plays a significant role in handling dangerous or repeat offenders. When someone has shown that they are a persistent threat to others, the focus shifts from rehabilitation or deterrence to straightforward prevention. The idea is that protecting innocent people justifies severe restrictions on the offender’s liberty.

Preventive punishment is also applied through mechanisms like restraining orders, electronic ankle monitors, or long-term surveillance. These don’t always involve prison but still aim to prevent future crimes by controlling the offender’s actions.

Still, this approach raises ethical and legal concerns. Should people be punished for crimes they might commit in the future? Does it violate basic human rights to incarcerate someone for being a “risk”? These are ongoing debates, especially in cases involving terrorism, chronic sexual offenders, or individuals with untreated mental illness.

Conclusion:

Punishment plays a crucial role in maintaining law, order, and social harmony within a society. It serves not only as a deterrent to crime but also as a means of reforming offenders, delivering justice, and upholding moral and legal standards. The various types of punishment—such as capital punishment, imprisonment, fines, and community service—are applied based on the nature and gravity of the offense.

The theories of punishment, including retributive, deterrent, reformative, preventive, and expiatory theories, provide different philosophical and practical approaches to justify and implement punishment. While the retributive theory emphasizes moral vengeance, the reformative theory focuses on transforming offenders into law-abiding citizens. Each theory contributes uniquely to the legal framework, often overlapping in modern judicial systems.

A balanced and just system of punishment, guided by a blend of these theories, is essential for safeguarding society, promoting justice, and ensuring that punishment leads to positive outcomes for both individuals and the community at large.