Introduction to State and Its Functions

What Is the State?

The word “state” often pops up in news, politics, and everyday conversation—but what exactly does it mean? At its core, the state is a political organization with centralized authority that governs a specific geographic territory. It enforces laws, collects taxes, maintains order, and represents itself in international affairs. But more than just a bureaucratic machine, the state is the arena where ideas of power, authority, and legitimacy play out.

From ancient empires to modern democracies and socialist regimes, the state has always served as the scaffolding for society. It’s the framework that defines how people interact with one another, how wealth is distributed, how justice is served, and how decisions that affect everyone are made. In political theory, especially, understanding the state is like having the blueprint for the building in which society operates.

Importance of Understanding the Functions of the States

Why should we even care how the state functions? Well, think about it. Every policy, every tax, every public service—from healthcare and education to roads and national defense—comes from decisions made by the state. Knowing the functions of the state helps us decode the world around us, vote more wisely, and even challenge systems that may be unjust or inefficient.

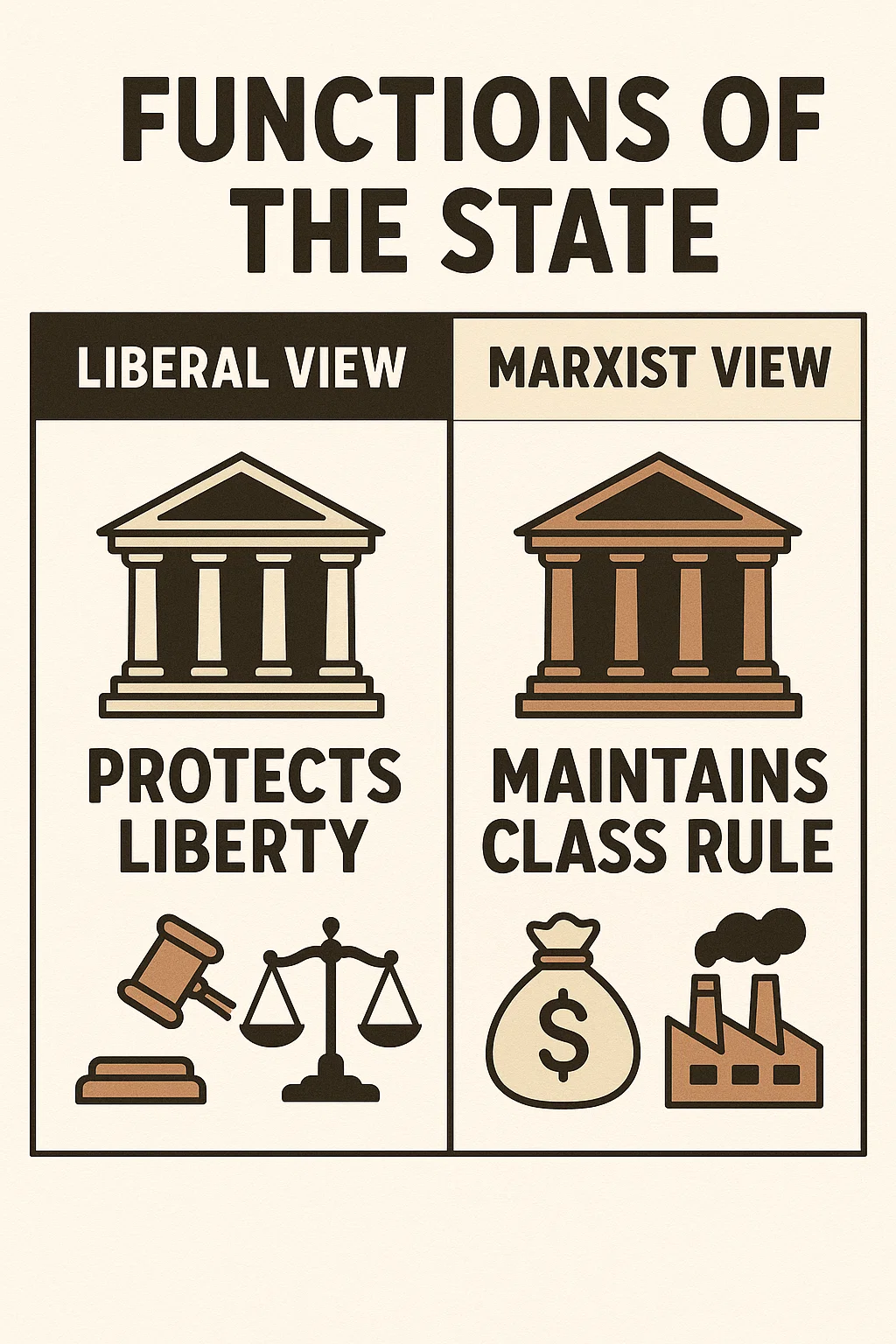

The idea of “state functions” goes beyond administrative duties. It dives into ideology: Why does the state do what it does? And depending on who you ask—a liberal or a Marxist—you’ll get two very different answers. Liberals see the state as a neutral protector of individual rights and freedoms, while Marxists see it as a tool used by the ruling class to maintain dominance over the working class.

So, to really get to the heart of politics and power, we need to explore these contrasting worldviews. Let’s dive into how liberals and Marxists understand the state and its functions.

The Liberal View of the State

Historical Origins of Liberalism

Liberalism didn’t just appear out of thin air. It emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially during the Enlightenment—a time when thinkers like John Locke, Adam Smith, and Montesquieu were challenging monarchies and divine rights with a fresh emphasis on reason, individual liberty, and limited government.

Locke argued that individuals have “natural rights” to life, liberty, and property, and that the state’s role is to protect these rights. In contrast to the absolute monarchies of the time, liberals believed the state should be a servant of the people, not their master. This was revolutionary. It laid the groundwork for modern democracies, constitutional governments, and capitalist economies.

Core Principles of the Liberal State

At its heart, liberalism revolves around a few fundamental beliefs:

- Individual Freedom: Every person is born free and equal, and the state exists to safeguard that freedom.

- Rule of Law: Laws should apply equally to everyone, including those in power.

- Separation of Powers: Dividing power between legislative, executive, and judicial branches prevents tyranny.

- Representative Democracy: Citizens elect officials to represent their interests.

These principles shape everything the liberal state does—from passing laws to regulating markets. But what exactly are the state’s main functions in this worldview?

Functions of the Liberal State

Protection of Individual Rights

First and foremost, the liberal state is a guardian of rights. Whether it’s your right to speak freely, worship as you choose, or own property, the state is expected to protect these freedoms from both internal and external threats. This includes maintaining public order through police, protecting borders with military forces, and ensuring courts are fair and impartial.

But there’s a delicate balance here. The state must intervene just enough to protect rights but not so much that it becomes oppressive. This balance defines the thin line between a liberal democracy and an authoritarian regime.

Limited Government and Rule of Law

Liberals are wary of unchecked power. That’s why they emphasize the importance of limited government. This doesn’t mean the state does nothing—it means it acts within clearly defined limits, guided by laws rather than the whims of rulers.

Think of it like a referee in a soccer match. The referee enforces rules, ensures fair play, and can penalize foul behavior—but doesn’t take part in the game. Similarly, the liberal state creates and enforces the legal framework within which society operates but refrains from dictating personal or economic choices.

Free Market and Economic Freedom

Economic liberalism is all about free markets. The state should protect private property and enforce contracts, but it shouldn’t interfere in the economy too much. According to thinkers like Adam Smith, the “invisible hand” of the market can do a better job than any central planner.

That said, modern liberal states recognize that pure laissez-faire capitalism can lead to exploitation and inequality. So, while the market is largely free, the state might regulate monopolies, ensure fair labor standards, or offer safety nets.

Welfare Functions and Social Justice

Over time, the liberal state evolved to take on welfare functions. Especially after the Great Depression and two World Wars, it became clear that some level of social safety net was necessary to maintain stability and fairness. This gave rise to the “welfare state” model, where the government provides education, healthcare, unemployment benefits, and pensions.

This doesn’t contradict liberal values; it expands them. The idea is that true freedom isn’t possible without basic needs being met. If you’re starving or uneducated, you’re not really free to pursue your goals. So, modern liberalism supports a mixed economy—balancing individual enterprise with collective support.

The Marxist V iew of the State

Historical Materialism and Class Struggle

Marxism doesn’t see the state as a neutral referee or protector of rights. Instead, it’s deeply rooted in historical materialism—a theory that economic structures shape every aspect of society, including politics, culture, and law. At the heart of this view is class struggle. Marx believed history is a continuous fight between the oppressors (those who own the means of production) and the oppressed (those who must sell their labor to survive).

According to Marx and Engels, the state arose as a result of this class conflict. It wasn’t created for the common good but rather to protect the interests of the ruling class. In capitalist societies, that means the bourgeoisie—those who own capital and industry. The state, in this view, isn’t above society but an instrument used by one class to dominate another.

The State as a Tool of Class Oppression

So, what exactly does that mean? Think about how laws are made and enforced. From a Marxist perspective, the laws we see in capitalist societies aren’t neutral—they reflect the interests of those in power. Property laws protect private ownership of factories and land, not the rights of workers. Police and courts often act to suppress labor movements or punish poverty rather than challenge the wealth gap.

Even seemingly democratic institutions like voting and free speech can be seen as masks that hide deeper economic inequalities. Marx called this “false consciousness”—the illusion that everyone is equal under the law when, in reality, the system is stacked in favor of the elite.

In short, the Marxist view paints the state not as a solution, but as part of the problem—a tool to maintain an unjust status quo.

Functions of the Marxist State

Maintenance of Class Rule

Under capitalism, Marxists argue that the main function of the state is to uphold the dominance of the bourgeoisie. This can take many forms:

Legal frameworks that prioritize private property over human need

Policing systems that protect corporate interests

Tax policies that favor the wealthy

Media control that shapes public opinion in ways that legitimize capitalist values

The state isn’t just complicit—it actively structures society to benefit the few at the expense of the many. Every institution, from schools to courts, plays a role in maintaining this class hierarchy.

Suppression of the Working Class

Marxists point to how the state reacts when workers demand change—through strikes, protests, or unions. In many cases, the response is forceful suppression. Whether it’s military intervention, arrests, or propaganda, the goal is to keep the working class in check.

For Marxists, this isn’t a failure of the system; it is the system. The state’s role is to keep labor cheap, maintain discipline among workers, and prevent collective action that might threaten capital’s control.

Centralized Planning and Collective Ownership

In contrast to the liberal model, where the market drives decisions, Marxists advocate for centralized planning. In a socialist state (the transitional stage before communism), the economy is run collectively to serve human needs rather than profit. Factories, banks, and natural resources are owned by the people, not private individuals.

The idea is to eliminate exploitation by removing the profit motive. With no capitalist class to skim surplus value, workers receive the full fruits of their labor. The state plays a critical role here, organizing production, setting quotas, distributing resources, and ensuring equality.

Transition to a Stateless Society

Ultimately, Marxists don’t want a stronger state forever. The long-term goal is communism—a classless, stateless society where there’s no need for government because there are no class divisions. This might sound utopian, but Marx saw it as the logical end of history once exploitation had been abolished.

This stage is known as the “withering away of the state.” Once class conflict disappears, and collective ownership is normalized, the mechanisms of repression (like police, prisons, and armies) become unnecessary. In their place, communities govern themselves through cooperative institutions.

Comparative Analysis of Liberal and Marxist Views

Contrasting Ideologies and Assumptions

At their core, liberalism and Marxism are worlds apart. Liberalism believes in individualism, private property, and a limited state that protects freedoms. Marxism, on the other hand, emphasizes collectivism, social ownership, and the idea that the state is inherently biased toward ruling-class interests.

Liberals assume that the state can be neutral and just. Marxists see it as structurally bound to serve the dominant class. While liberals trust reforms and institutions, Marxists seek revolution and systemic change.

This difference isn’t just academic—it shapes how each ideology proposes to solve issues like poverty, inequality, and justice.

Views on Democracy and Political Power

Liberals champion representative democracy, free elections, and pluralism. They believe that democracy can work within capitalism and that the system can be corrected through civic engagement, legal reform, and public debate.

Marxists, however, are skeptical. They argue that capitalist democracies are only democratic in form, not in substance. Since wealth heavily influences media, campaigns, and political access, the working class often has little real power. As Lenin put it, liberal democracy is a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie” wrapped in democratic packaging.

Instead, Marxists favor proletarian democracy—workers’ councils, participatory governance, and direct control over economic and political decisions.

Economic Policy Differences

Economically, liberalism promotes free markets, private ownership, and limited regulation. The belief is that competition and innovation thrive best under minimal state interference.

Marxists reject this outright. They view capitalism as inherently exploitative and unstable, pointing to recurring financial crises, widening inequality, and environmental degradation as symptoms of a broken system.

Their solution? Replace profit-driven production with planned economies where the state ensures equitable distribution, eliminates wasteful competition, and serves the collective good.

Human Rights and Freedom: Divergent Interpretations

Here’s where things get especially contentious. Liberals define freedom in negative terms—freedom from interference. That’s why they support property rights, free speech, and minimal state control.

Marxists redefine freedom in positive terms—freedom to live a dignified, fulfilling life. From their view, you’re not truly free if you’re unemployed, underpaid, or homeless, no matter how many rights you technically have.

So, where liberals see too much state power as a threat to liberty, Marxists see it as a necessary tool (at least temporarily) to achieve real equality and freedom for all.