Written by advocate Aniket Pratap Singh, BA.LLB(Hons)

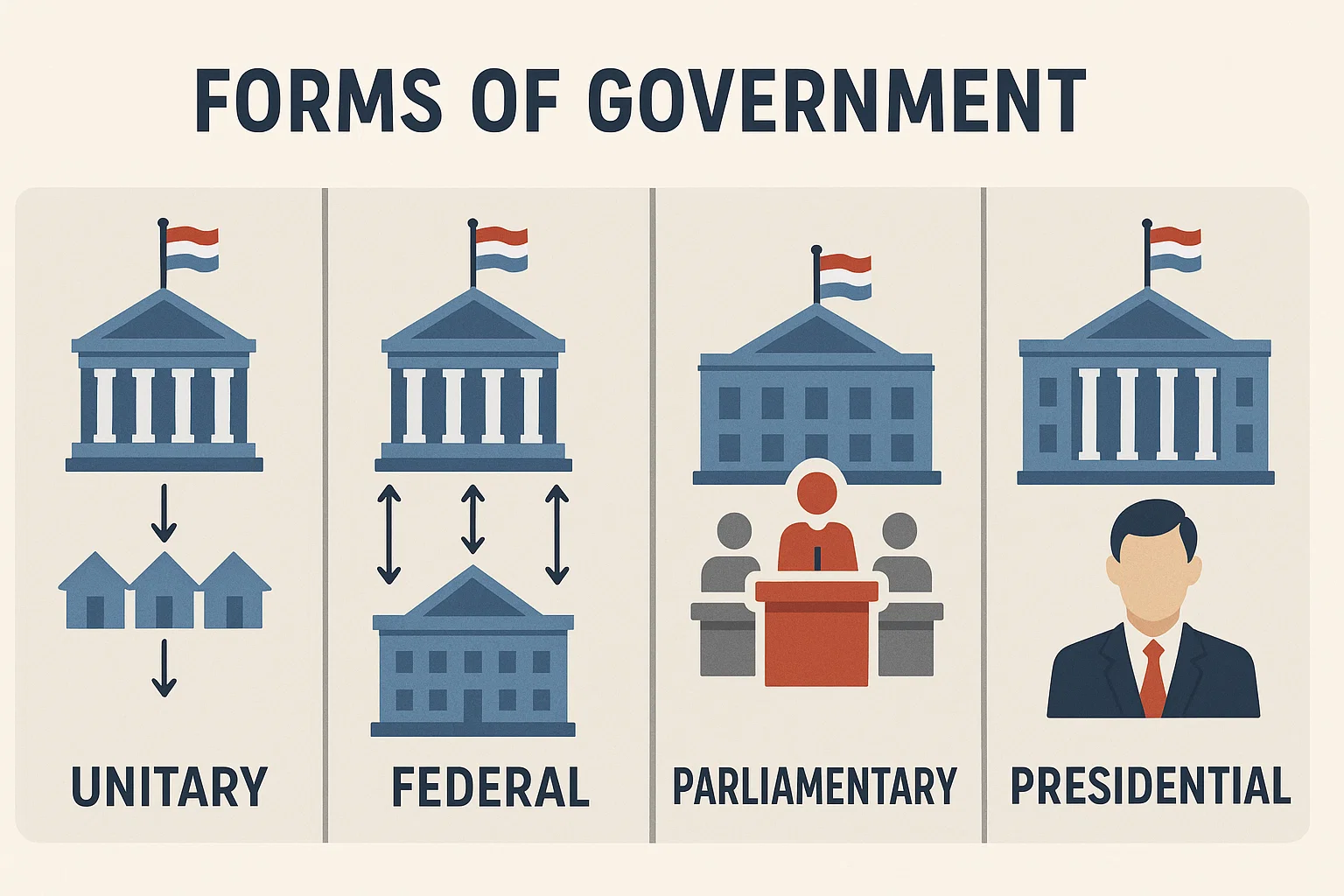

When we think about governments, what often comes to mind is the person in charge—maybe a president or a prime minister. But the real strength of a nation’s governance lies in its system. Whether it’s centralized or decentralized, parliamentary or presidential—each system carries a unique approach to how power is distributed, decisions are made, and the people are served. In this article, we’ll break down these systems into their core components—Unitary, Federal, Parliamentary, and Presidential—and explore how they shape the lives of people and nations across the globe.

Unitary vs Federal Government

Understanding Unitary Government

In a unitary system, all the power is concentrated in a central government. Think of it as a one-size-fits-all approach to governance. The central authority holds supreme power, and any local governments exist purely to implement the center’s decisions. These local bodies may have administrative authority, but not legislative autonomy.

What makes unitary governments effective is their simplicity. Laws are uniform across the country. There’s a single constitution, single legislature, and typically one judiciary system. This uniformity ensures that policy implementation is swift and coordinated.

Take the United Kingdom, for example. Though it now has devolved powers for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, it remains essentially a unitary system. The UK Parliament holds the right to make or unmake any law, and local authorities function at the behest of the central government.

Understanding Federal Government

Unlike unitary systems, federal governments are all about shared power. Federalism involves dividing the authority between a central government and various constituent states or provinces. Each level of government operates independently in its domain, as defined by a written constitution.

The strength of federalism lies in its ability to accommodate diversity. In large countries with varied cultures, languages, and economic structures, federal systems allow local governments to cater to their region’s unique needs while still being part of a unified nation.

Take the United States: the federal government has jurisdiction over defense and foreign affairs, while states handle education, healthcare, and law enforcement. India, although officially a “Union of States,” operates with a quasi-federal structure where powers are distributed across central and state governments with some overlaps and special provisions.

Features, Merits, and Demerits of Unitary Government

Features:

Single central authority

Uniform laws and policies

No constitutional division of power

Merits:

Efficiency in Governance: Decisions can be made quickly without needing coordination among various levels of government.

Consistency: Laws are the same across the entire nation, creating clarity and uniformity.

Cost-Effective: Less bureaucratic duplication means lower administrative costs.

Demerits:

Risk of Over-Centralization: Local issues may be ignored in favor of national priorities.

Lack of Local Autonomy: Citizens may feel disconnected from decision-making processes.

Bureaucratic Bottlenecks: While it may seem faster, overreliance on the central government can create delays due to heavy workloads and red tape.

In essence, a unitary government thrives in smaller or culturally homogeneous nations where one policy can work for everyone. But in a vast, diverse country, it can feel like trying to fit a square peg in a round hole.

Features, Merits, and Demerits of Federal Government

Features:

Two or more levels of government

Constitutionally defined powers

Independent judiciary

Merits:

Local Representation: Regional governments can address the specific needs of their populations.

Checks and Balances: Shared power reduces the chance of authoritarian rule.

Encourages Innovation: States or provinces can act as policy labs, experimenting with solutions that, if successful, can be adopted nationwide.

Demerits:

Duplication of Efforts: Overlapping responsibilities can lead to inefficiencies.

Intergovernmental Conflicts: Power struggles between center and states can stall progress.

Uneven Development: Wealthier states might progress faster, creating regional disparities.

Federalism suits large and diverse countries but comes with its own set of challenges that require constant negotiation and cooperation among various levels of government.

Examples of Unitary and Federal Systems

Let’s take a closer look at real-world examples to cement our understanding.

United Kingdom (Unitary): Despite recent devolutions of power to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the UK Parliament retains the authority to legislate on all matters. It’s a strong model of centralized governance, historically effective in maintaining national unity.

India (Federal): India is often described as a “quasi-federal” state because while it has a written constitution dividing powers between the center and states, the central government holds overriding authority in many areas. Emergency provisions can also turn India effectively into a unitary state.

United States (Federal): The U.S. follows a true federal model. Each state has its own constitution, governor, and legislature. The federal constitution clearly delineates what the federal government can and cannot do, reserving other powers for the states.

Parliamentary vs Presidential Systems

Structure and Functioning of Parliamentary System

The parliamentary system is one of the most widely adopted forms of governance in the world. In this model, the executive branch derives its legitimacy from the legislative branch (parliament) and is accountable to it. Simply put, the people elect members of parliament, and the party (or coalition) with a majority forms the government.

At the heart of this system is the Prime Minister, who acts as the head of government. The ceremonial head of state, such as a monarch or president, has limited real power. This setup fosters close cooperation between the executive and legislative branches, since the government needs parliamentary support to stay in power.

Key Features:

The Prime Minister and Cabinet are drawn from the legislature.

Fusion of powers between executive and legislative branches.

The government can be dissolved by a vote of no confidence.

The head of state is different from the head of government.

Advantages:

Responsiveness and Accountability: Ministers are directly answerable to parliament, making it easier to question or remove them.

Collective Decision-Making: Since decisions are made in a cabinet, it prevents the concentration of power in one individual.

Efficient Law-Making: Fusion of powers allows smoother legislative processes, particularly when the ruling party has a majority.

Disadvantages:

Instability: Coalition governments can collapse quickly if support is withdrawn.

Lack of Separation of Powers: Overlap between executive and legislative roles can weaken checks and balances.

Domination by the Majority Party: A strong majority can override minority voices with ease.

This system thrives in environments where political consensus is valued and where frequent accountability is preferred over rigid structures.

Structure and Functioning of Presidential System

In contrast, the presidential system is a model where the executive is completely separated from the legislature. The president is elected independently of the legislature, serves a fixed term, and holds significant powers as both the head of state and head of government.

This form is built on a strong emphasis on the separation of powers. The legislative, executive, and judiciary branches operate independently, maintaining a system of checks and balances. The President cannot dissolve the legislature, and vice versa.

Key Features:

Fixed tenure for the President.

Clear separation between the executive and legislative branches.

President appoints Cabinet, but members usually can’t be sitting legislators.

The President is directly elected by the people or an electoral college.

Advantages:

Stability: Fixed tenure provides predictable governance.

Separation of Powers: Reduces the risk of legislative dominance or executive overreach.

Direct Mandate: The President enjoys a direct mandate from the people, enhancing legitimacy.

Disadvantages:

Risk of Gridlock: Conflicts between the executive and legislature can result in legislative deadlock.

Lack of Accountability: A President is not easily removed, even when they lose popular support.

Potential for Authoritarianism: Concentration of power in a single leader, especially if checks are weak, can be dangerous.

This system often suits countries with strong democratic institutions and a culture of political checks and balances.

Comparative Case Study: India’s Parliamentary System

India is the world’s largest democracy and follows the Westminster parliamentary model, albeit with some local adaptations. The President of India is the nominal head of state, while the Prime Minister is the de facto leader of the executive branch. The Parliament comprises two houses: the Lok Sabha (House of the People) and the Rajya Sabha (Council of States).

The Prime Minister is elected by the majority party or coalition in the Lok Sabha. Cabinet ministers are also drawn from Parliament and must retain the confidence of the lower house to remain in power.

Key Characteristics:

A bicameral legislature.

President with limited powers, mostly ceremonial.

Prime Minister accountable to Parliament.

Collective responsibility of the Cabinet.

Strengths:

Representation: MPs are directly elected, reflecting the people’s will.

Flexibility: The system adapts well to coalition governments and shifting political alliances.

Accountability: Regular sessions, debates, and no-confidence motions ensure government responsiveness.

Challenges:

Political Fragmentation: Coalition governments can weaken decisive governance.

Regional Politics: State parties play a dominant role, often affecting national policies.

Patronage and Party Loyalty: MPs often follow party lines, reducing independent thinking.

Overall, India’s parliamentary system manages to balance democracy with diversity, though it often requires political negotiations and compromise.

Comparative Case Study: USA’s Presidential System

The United States follows a presidential system as established by its 1787 Constitution. The President is elected for a four-year term and serves as both head of state and government. This system emphasizes independence between the three branches: Executive, Legislative (Congress), and Judiciary.

Congress itself is bicameral, comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate. Laws passed by Congress must be approved or vetoed by the President. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court acts as a final arbiter in disputes and can overturn laws deemed unconstitutional.

Core Elements:

Independent election of the President.

Separation of powers and checks and balances.

Limited terms and power constraints.

Strengths:

Autonomy of Leadership: The President can act decisively without legislative interference.

Stability: Terms are fixed and not reliant on legislative confidence.

Checks and Balances: Each branch can limit the powers of the others.

Weaknesses:

Legislative Deadlock: Divided government often results in gridlock.

Impeachment is Difficult: Removing an unpopular President requires a high threshold.

Campaign Complexity: Presidential elections are long, expensive, and heavily politicized.

The U.S. model thrives on institutional clarity and individual leadership but often suffers from political polarization and bureaucratic impasses.

Which System is Best?

Evaluating Based on Governance Efficiency

One of the most crucial benchmarks for any political system is how efficiently it governs. Governance efficiency includes the speed of decision-making, implementation of policies, and response to crises. In this regard, both unitary and parliamentary systems tend to outperform their counterparts under specific conditions.

Unitary systems, thanks to centralized power, are often more agile. Policies are formulated and implemented quickly without the need for consensus from regional entities. This can be incredibly useful during national emergencies or when uniformity is crucial.

Similarly, parliamentary systems tend to be efficient when a single party holds a clear majority. Since the executive and legislative branches are interconnected, there’s less gridlock. Governments in such systems can pass laws more swiftly and execute policies with minimal delay.

On the other hand, federal and presidential systems may experience slower decision-making processes. In a federal system, laws passed by the central government often require coordination with state authorities, which can create bottlenecks. Likewise, in presidential systems like that of the USA, opposition control of the legislature can paralyze the executive branch—often leading to “government shutdowns” or legislative gridlocks.

That said, slow governance is not always a flaw. It can be a sign of a deliberative, democratic process where diverse opinions are heard before decisions are made. So, if governance efficiency is prioritized, unitary and parliamentary models may have the edge—but at the potential cost of inclusivity.

Representation and Accountability

Representation and accountability are the cornerstones of any democratic system. Citizens should not only feel represented in government but also be able to hold their leaders accountable.

Federal systems are generally better at representation. With state or provincial governments having authority, local populations can influence policies more directly. This model empowers marginalized or minority groups to have a stronger voice at the regional level, thereby promoting inclusivity.

Similarly, parliamentary systems foster accountability. Since the executive is part of the legislature, it’s regularly questioned during parliamentary sessions. A vote of no confidence can remove the entire government if it loses majority support, which acts as a powerful tool of accountability.

In contrast, presidential systems, although featuring direct elections, are sometimes less responsive in between elections. The President cannot be easily removed except in cases of serious misconduct. This fixed tenure can be both a strength—ensuring stability—and a weakness—limiting accountability during crises.

Unitary systems, depending on how they are structured, can either enhance or diminish representation. In highly centralized forms, minority interests may be overlooked. However, in unitary states with strong local councils or devolved administrations (like the UK’s devolution), this can be mitigated.

In essence, the best system for representation and accountability often depends on the cultural and political maturity of the nation. No system is inherently better—it’s all about how it’s implemented.

Adaptability to Cultural and Regional Diversity

When evaluating political systems for large, culturally diverse nations, adaptability becomes essential. A government must be flexible enough to address regional identities, languages, customs, and socio-economic differences.

Federal systems excel in this regard. They’re built to handle regional complexity. Take India, for instance: 22 officially recognized languages, dozens of ethnic groups, and vast socio-economic differences are all accommodated through a federal structure. States have significant autonomy over education, health, and language policies, allowing them to function in ways best suited to their local population.

Unitary systems may struggle with such diversity. A central policy often cannot capture the nuances of various regional needs. However, unitary governments can still show adaptability through decentralization or devolution, granting powers to local governments. This is seen in the UK, where Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have their own parliaments or assemblies.

Parliamentary systems can adapt well if they include coalition governance, enabling multiple parties—often representing different communities or ideologies—to participate in decision-making. Countries with strong multi-party systems benefit from this inclusivity.

On the flip side, presidential systems often face rigidity. A winner-takes-all model can alienate minority groups, especially in ethnically or culturally divided societies. If the executive does not represent the diversity of the nation, tensions may rise.

In conclusion, if cultural and regional inclusivity is a priority, federal-parliamentary hybrids may offer the best of both worlds—representation, accountability, and adaptability.

Conclusion

Summary of Differences and Takeaways

Choosing the “best” system of government isn’t about picking a winner. Each model—unitary, federal, parliamentary, or presidential—offers distinct advantages and faces unique challenges. The decision lies in aligning a system’s strengths with a country’s specific context.

Unitary systems provide simplicity, centralized authority, and consistent policies. Ideal for smaller, homogeneous nations but potentially less responsive to regional diversity.

Federal systems promote representation, regional autonomy, and policy flexibility but can become complex and slow.

Parliamentary systems ensure government accountability and policy responsiveness, especially with a strong majority, but may face instability in coalitions.

Presidential systems offer clear separation of powers and fixed terms for stability but risk gridlock and less immediate accountability.

Different nations have successfully adopted different models based on their needs. The United Kingdom thrives under a unitary parliamentary system. The United States operates effectively with a federal presidential model. India has embraced a unique mix—federal in structure and parliamentary in function.

Final Thoughts

In a rapidly changing world, the effectiveness of governance may soon depend less on the traditional classifications of systems and more on their hybrid adaptability. Nations might begin blending elements from each system—centralized control with local autonomy, elected executives with parliamentary accountability, or federal structures with presidential checks.

The goal should always be to create governments that are inclusive, efficient, transparent, and responsive to the needs of their people. After all, the structure is only as good as the vision and will of those who operate within it.