Introduction

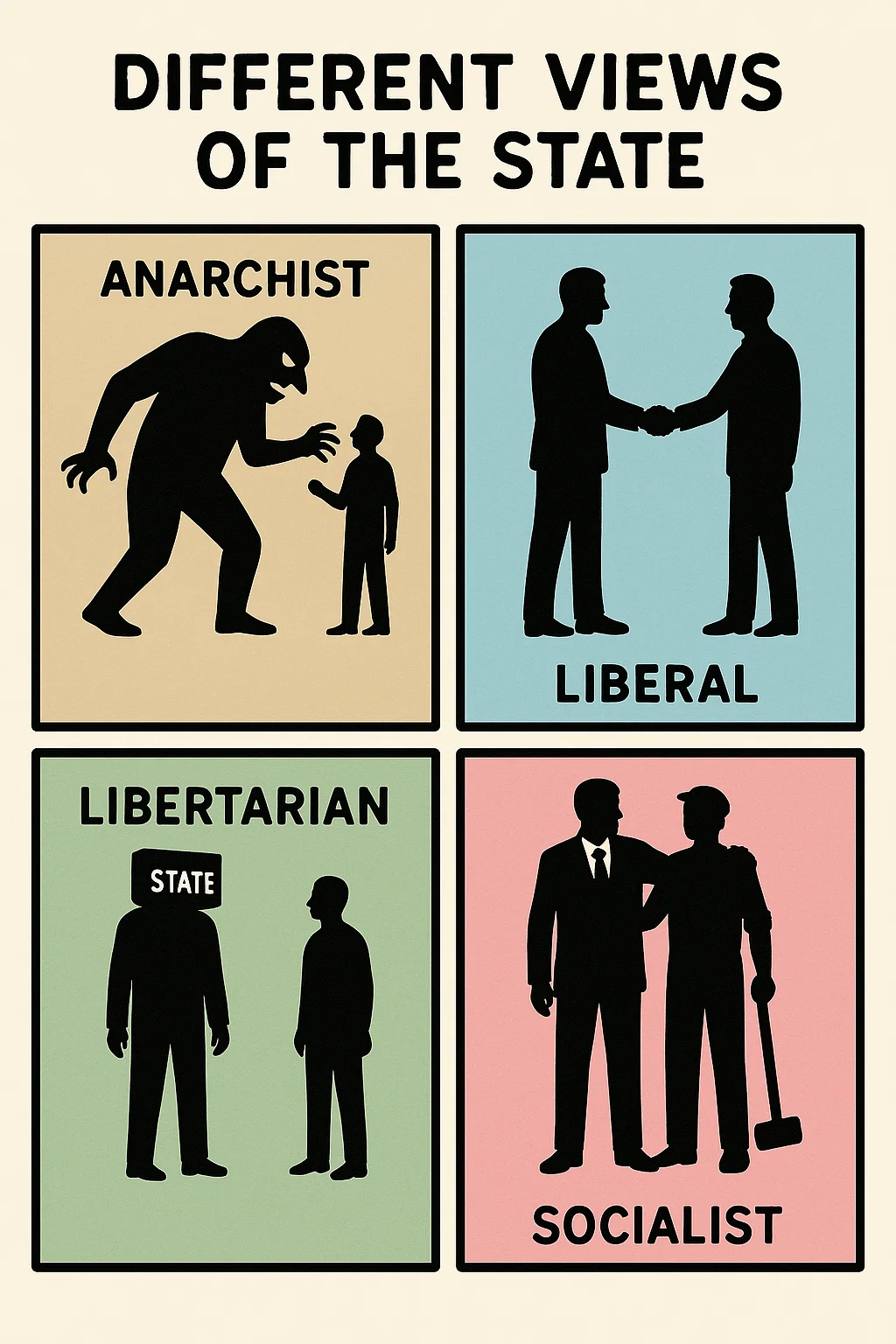

What is the state? At first glance, it’s a simple term—something we all recognize as part of our lives. But scratch beneath the surface, and you’ll uncover a range of deep, sometimes opposing views shaped by centuries of philosophy, religion, economics, and political theory. The state, depending on who you ask, could be a neutral referee, an instrument of oppression, a moral being, a religious duty, or a guardian of divine law.

Understanding these different ideologies helps us make sense of how various societies operate and why they prioritize certain values over others. Whether you’re discussing social justice, governance, individual rights, or economic models, the view of the state fundamentally shapes those conversations.

In this article, we’ll dive deep into five powerful lenses through which the state has been interpreted: Liberal, Marxist, Idealist, Classical Hindu, and Islamic. Each of these viewpoints offers a comprehensive framework of how power should be exercised, what the role of government ought to be, and where individuals fit in. Ready for a journey across time and thought? Let’s begin.

The Liberal View of the State

Origins and Historical Development

The liberal view of the state emerged out of Enlightenment thinking in Europe, gaining traction between the 17th and 19th centuries. It arose largely as a reaction against monarchic absolutism and religious authoritarianism. Thinkers like John Locke, Adam Smith, and later John Stuart Mill were instrumental in shaping the intellectual foundation of liberalism. Their ideas were bolstered by the socio-political upheavals of the time—like the Glorious Revolution in England and the American and French Revolutions—that called for limited government and the protection of individual freedoms.

Liberalism redefined the role of the state. No longer a divine right, the state became a social contract—a mutual agreement between free individuals to form a government for the protection of life, liberty, and property. This view transformed the nature of governance from rule by divine or hereditary mandate to governance by consent.

Core Principles of Liberalism

At the heart of liberalism lies the value of the individual. The liberal state exists not to control people but to protect their inalienable rights. Here’s what the liberal view typically emphasizes:

Individual Freedom: Citizens have the right to act freely, so long as they don’t infringe on others’ rights.

Rule of Law: Laws apply equally to all and are not subject to the whims of rulers.

Limited Government: The state should only intervene where necessary—primarily in ensuring security, justice, and property rights.

Representative Democracy: Government must be accountable and chosen through free and fair elections.

Market Economy: Economic freedom is just as vital as political freedom.

These principles form the philosophical bedrock of most Western democracies today.

Role of the State in Liberal Thought

From a liberal perspective, the state is a necessary but limited actor. It is not the center of society but a facilitator of peaceful coexistence. The state should:

Act as an impartial arbiter in disputes.

Ensure national defense and public safety.

Guarantee civil rights and property rights.

Provide public goods that markets can’t efficiently supply.

Crucially, liberals distrust concentrated power. Whether it resides in government or private entities, too much control is a threat to liberty. Therefore, mechanisms like checks and balances, a free press, and an independent judiciary are essential to maintaining a healthy liberal state.

Major Thinkers and Contributions

John Locke: Advocated the social contract and natural rights; laid the groundwork for constitutional democracy.

Adam Smith: Argued for economic freedom and limited state interference in markets.

John Stuart Mill: Pushed for expanded individual liberty and argued for the protection of minority rights in democracies.

Their contributions remain embedded in modern constitutional democracies and influence institutions like the United Nations, the U.S. Constitution, and the European Union.

The Marxist View of the State

Philosophical Roots in Dialectical Materialism

Marxist theory is not just a political stance; it’s a philosophical lens through which history, society, and economics are analyzed. Rooted in the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Marxism is built upon dialectical materialism—the belief that material conditions, particularly economic relationships, drive historical development.

Marx believed that human history was a continuous struggle between classes: the oppressors and the oppressed. This conflict isn’t random; it’s structured by the economic base (who owns what and who works for whom). The state, in Marxist theory, arises as a tool to maintain this economic order.

State as an Instrument of Class Domination

According to Marx, the state is not a neutral force. It exists primarily to serve the interests of the ruling class—in capitalism, that’s the bourgeoisie (owners of production). The state:

Enforces laws that protect private property.

Uses police and military to suppress dissent.

Controls ideology through education, media, and religion.

In a capitalist society, the state perpetuates inequality under the illusion of fairness. This perspective sharply contrasts with the liberal view of the state as a neutral guardian of rights.

The Withering Away of the State

Here’s where Marxist theory takes a unique turn. The state, according to Marx, is not permanent. In a truly classless society—where there’s no exploitation—there would be no need for a coercive state. Thus, after a period of proletarian revolution and socialism, the state will “wither away.”

Marx envisioned a communist society where people governed themselves through direct democracy and communal ownership of resources. No state, no classes, just equality.

Key Marxist Theorists and Their Influence

Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: Originators of the theory; wrote The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital.

Vladimir Lenin: Adapted Marxism for revolutionary application in Russia, emphasizing a “vanguard party.”

Antonio Gramsci: Highlighted the role of cultural hegemony in maintaining state power.

These thinkers inspired revolutions and regimes in Russia, China, Cuba, and beyond, reshaping global politics throughout the 20th century.

The Idealist View of the State

State as a Moral and Ethical Entity

Unlike the liberal and Marxist views which focus on individual rights or economic relations, the idealist perspective sees the state as something much grander—a moral and spiritual organism. To idealists, the state is not just a mechanism for governance or protection of property; it’s a living entity that represents the highest expression of ethical life. The state is the collective manifestation of reason, purpose, and will.

This view argues that individuals can only achieve true freedom through their participation in the state because it embodies the common good. The state becomes a teacher, a guide, and a guardian of morality. It does not merely protect rights; it cultivates virtue.

Idealism challenges the liberal idea of freedom as mere non-interference. Instead, it promotes positive freedom—the idea that people are truly free when they live in harmony with ethical laws and duties.

The Influence of Hegelian Philosophy

The idealist conception of the state owes much to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a 19th-century German philosopher. Hegel viewed history as a rational process through which human freedom evolves. He believed that the state was the highest form of social life, where freedom becomes reality.

According to Hegel, the state isn’t a creation of individuals—it precedes them and shapes them. Through laws, institutions, and civic duties, the state elevates human life from mere self-interest to a universal ethical order. In his Philosophy of Right, Hegel famously declared: “The State is the actuality of the ethical Idea.”

This concept deeply influenced European thinkers and political leaders, especially in Germany and Italy, who saw the state not as an oppressor but as an enabler of moral progress.

Individual and State Relationship

In idealism, individuals and the state are interdependent. One does not exist without the other. Unlike liberalism, which emphasizes individual autonomy, idealism stresses that individuals realize their true selves only through their relationship with the state.

This doesn’t mean idealism promotes authoritarianism—at least not inherently. It supports a state that reflects the rational will of its people and works for their moral upliftment. However, this view can be (and has been) manipulated by totalitarian regimes to justify absolute control in the name of unity and moral order.

Here, freedom is a function of responsibility. Rights come with duties, and the state ensures both are honored.

Contributions of Idealist Thinkers

G.W.F. Hegel: The father of idealist theory of state; saw it as the highest realization of human spirit.

T.H. Green: A British philosopher who merged Hegelian ideas with liberalism, advocating for a more active state promoting welfare and education.

Giuseppe Mazzini: An Italian nationalist who linked the idealist state to the concept of national unity and divine destiny.

Their legacy lives on in welfare states and civic republican ideologies that emphasize duty, community, and ethical citizenship.

The Classical Hindu View of the State

Dharma and the Foundation of State Authority

The classical Hindu perspective sees the state not merely as a political institution but as a dharmic order—a divine and moral structure meant to uphold righteousness (dharma). Rooted in ancient scriptures like the Vedas, Upanishads, Manusmriti, and the Mahabharata, the Hindu view integrates spirituality, morality, and practical governance.

In this worldview, dharma is the foundation of all societal relationships. It defines not only personal ethics but also the duties of rulers and citizens. The state exists to ensure that dharma prevails over adharma (chaos or evil). It is not an instrument of coercion but a guardian of cosmic and social harmony.

Kings and rulers are seen as servants of dharma, and their legitimacy depends on their ability to uphold it. Failure to do so is not just a political failure but a cosmic disorder.

The Role of the King and Governance

In classical Hindu thought, the king (raja) holds a central and sacred role. While the king wields immense power, his actions are guided by shastras (scriptures), and his prime duty is to protect the people and uphold dharma. His responsibilities include:

- Enforcing law and order

- Protecting the kingdom from external threats

- Administering justice fairly

- Promoting prosperity through proper taxation and welfare

- Supporting Brahmins and learned men to guide the state spiritually

The king was advised by ministers, priests, and scholars, creating a quasi-democratic advisory system. Yet, the monarch remained supreme, akin to a trustee rather than a dictator.

It was also expected that kings perform yajnas (rituals) and sacrifices to ensure the spiritual well-being of the realm. Thus, governance was both administrative and religious.

Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Political Realism

A stark contrast to the idealistic tone of dharmic rule is Kautilya’s Arthashastra, an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economics, and military strategy. Written around 300 BCE, it offers a realist and sometimes even Machiavellian view of the state.

Kautilya (also known as Chanakya) presents the king as a pragmatic ruler whose ultimate goal is to preserve the state’s power. The Arthashastra outlines:

- Methods of espionage and internal security

- Foreign policy based on diplomacy and warfare

- Economic management including taxation, trade, and agriculture

- Justice system based on evidence and deterrence

Despite its realism, Kautilya does not abandon dharma. Instead, he sees statecraft as the art of balancing pragmatism with morality, always aiming for the prosperity and security of the people.

Society and State Interdependence in Hindu Thought

The Hindu view of the state is holistic and integrated. It doesn’t separate religion, morality, and politics—they are all parts of the same cosmic order. Society is stratified into varnas (classes) and ashramas (life stages), each with its own set of duties and rights.

The state’s role is to ensure that each group functions in harmony, maintaining social balance. This makes the Hindu view highly ethical but also hierarchical, with social mobility often restricted.

In sum, the classical Hindu view combines spiritual ethics, divine law, monarchy, and realism, making it one of the most complex and layered state theories in human history.

The Islamic View of the State

Integration of Religion and Politics

In Islam, there is no division between religion and politics. The Islamic state is conceived as a system where governance is inseparably tied to divine law (Shariah). Unlike secular models where religion is private and personal, the Islamic view sees the state as a moral and religious order responsible for implementing Allah’s commands on earth.

The ultimate sovereignty in an Islamic state belongs not to the people, but to Allah. The government merely administers laws already laid out in the Qur’an and Hadith (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad). This system, far from being theocratic in a priestly sense, is more accurately described as a legal-moral system where leaders are accountable to divine authority, not personal whim.

The Prophet Muhammad himself was both a spiritual guide and a political leader. His model in Medina established the blueprint for Islamic governance—uniting tribes, enforcing justice, managing treaties, and leading armies, all under the umbrella of divine guidance.

The Concept of Shura and Caliphate

While sovereignty belongs to Allah, Islamic governance encourages consultation (Shura) and collective decision-making. This principle is embedded in the Qur’an and supports a semi-democratic structure where leaders are expected to consult with advisors and the community before making decisions.

Historically, the Caliphate was the political system that followed the Prophet’s death. Caliphs were not kings but successors of the Prophet, chosen for their piety, knowledge, and leadership. While the method of selecting caliphs varied, the ideal was clear: a ruler must uphold justice, protect the faith, and serve the ummah (Muslim community).

Shura is not equivalent to Western-style democracy, but it plays a role in legitimizing leadership through community consensus. Many Islamic scholars today argue that modern democratic principles can align with Shura, provided they respect Islamic values.

Justice and Governance in Islamic Thought

Justice (Adl) is the cornerstone of the Islamic state. The Qur’an commands believers to “stand firm for justice, even against yourselves” (4:135). An Islamic government is duty-bound to ensure:

Fair distribution of wealth

Eradication of corruption and exploitation

Protection of the weak, orphans, and women

Implementation of Zakat (obligatory charity)

Equal treatment under the law

Justice isn’t just legal—it’s spiritual. Leaders are seen as shepherds of their people, and misrule is considered both a worldly and spiritual failure. Corrupt rulers, in Islamic eschatology, are destined for divine punishment.

Unlike secular states that separate ethics from politics, the Islamic model demands that governance be infused with moral integrity.

Key Islamic Scholars and State Theory

Al-Mawardi: In his Al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya, he laid out guidelines for the powers and responsibilities of Islamic rulers.

Ibn Khaldun: A sociologist-historian who emphasized the role of social cohesion (asabiyyah) in maintaining state stability.

Maulana Maududi: A 20th-century scholar who proposed the concept of a theo-democracy, blending Islamic values with democratic principles.

Together, these thinkers present the Islamic state as a balance between divine commandments and human consultation, aiming for a just and virtuous society.

Comparative Analysis of All Five Views

Commonalities and Contrasts

Let’s pause and zoom out. These five perspectives—Liberal, Marxist, Idealist, Classical Hindu, and Islamic—might seem worlds apart, but they all attempt to answer the same core question: What is the role of the state in human life?

Here’s how they stack up on key themes:

| Aspect | Liberal | Marxist | Idealist | Hindu | Islamic |

| Sovereignty | People | Working class | Ethical Spirit | Dharma | Allah |

| Freedom | Individual rights | Class liberation | Moral development | Duty-bound | Submission to divine law |

| Law | Man-made, secular | Class-based | Ethical expression | Dharma-shastra | Shariah |

| Religion & State | Separate | A tool of ruling class | Optional | Integrated | Integrated |

| Economic Role | Limited | Central planning | Regulated by ethics | Welfare-oriented | Zakat, anti-usury |

| Justice | Legal fairness | Class equality | Moral justice | Cosmic order | Divine justice |

While liberalism and Marxism are more secular and materialist, the other three incorporate ethical or spiritual dimensions. Liberal and Islamic states emphasize rule of law, but the source of law differs: human reason vs. divine command.

The Idealist and Hindu views are more metaphysical, suggesting that the state is not just a contract or structure but a moral or cosmic necessity.

Role of Religion, Economy, and Ethics

Religion: It is central in Hindu and Islamic models, optional in idealism, and rejected in liberal/Marxist systems.

Economy: Marxism advocates total state control, liberalism prefers free markets, and Islamic/Hindu models stress ethical wealth management.

Ethics: All but Marxism embed morality in governance—some divinely, some philosophically.

The diversity of thought illustrates that no single view has a monopoly on truth. Each reflects the needs, values, and realities of the society it emerged from.

Implications for Modern Governance Models

In today’s globalized world, we often see hybrid models. Secular democracies borrow from liberalism but use state intervention (a Marxist concept). Some Muslim countries attempt Islamic democracy, while India blends liberal and Hindu legal principles.

- Understanding these views helps us:

- Navigate multicultural governance

- Appreciate historical context in politics

- Avoid one-size-fits-all political solutions

No theory is perfect. Each has its strengths and blind spots. The task of modern governance is to balance these legacies to meet today’s challenges—inequality, climate change, spiritual emptiness, and civil unrest.

Conclusion

The state, as we’ve seen through the lenses of Liberalism, Marxism, Idealism, Classical Hinduism, and Islam, is far more than a bureaucratic machine or a political boundary. It is a living idea—shaped by history, culture, philosophy, economics, and religion. These five diverse views give us a panoramic understanding of how different societies conceive power, justice, freedom, and responsibility.

The liberal view sees the state as a neutral protector of individual freedoms. It believes in limited government, civil liberties, and democratic values. It’s a framework that dominates modern Western democracies and emphasizes individualism and rational law.

In contrast, the Marxist view is deeply skeptical of the state as it exists in capitalist societies. To Marxists, the state is a tool of class oppression and must eventually be dismantled to achieve a classless, stateless society. It provides a radical critique of inequality and pushes for systemic economic transformation.

The idealist view, rooted in philosophy, imagines the state as a moral community—a vessel for ethical development. It bridges individual purpose with collective good, viewing the state not just as a legal entity but as an expression of the human spirit striving toward freedom and virtue.

The Classical Hindu view intertwines spirituality, duty, and political realism. The state is not a secular institution but one founded on Dharma—a divine moral order. It provides a unique fusion of ethics and pragmatism, where rulers are bound to spiritual and social duties.

Lastly, the Islamic view integrates faith and governance. The state serves as an instrument to enforce divine law and uphold justice as outlined by Shariah. Its foundation lies in submission to Allah, with leaders held accountable to both divine standards and their community.

Together, these views don’t just help us understand different types of states—they help us understand different ways of being human. Each model emerges from a deep well of tradition and philosophical reasoning. As citizens of a rapidly globalizing world, engaging with these ideas doesn’t just make us smarter—it makes us wiser, more empathetic, and better equipped to shape the future.